Exhibitions | ZeftLand

ZeftLand

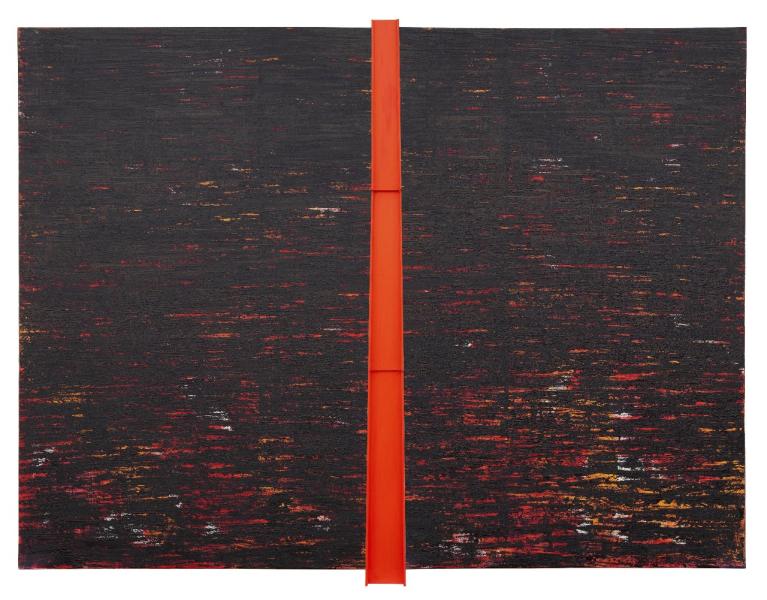

In the beginning of the First Intifada, in the years between 1988 and 1990, the occupying Israeli army enforced a curfew on the city that lasted more than 20 days. I was 10 years old then. We heard nothing during those days of imprisonment except for the loud rumbling of army vehicles. A repulsive smell seeped into our houses and we didn’t even have the right to look through the windows to see what was happening outside.

On the morning of the day that the curfew was lifted, I went out with my father, holding his hand, to see that everything over three meters high had been spray painted black, including all the walls and shop doors. Even the bottom third of the palm tree, which stood at the heart of our neighborhood, was black… So I asked my father, what is all this? He answered, zeft—tar—and I asked him why? He said, …in order to cover the graffiti on the walls and to prevent anyone from writing again, which they consider incitement. I was silent for a bit, my father was too, while that horrific scene captured our eyes. After a moment I asked my father, I wonder, have they sprayed the sea too? My father looked at me, smiling, and said possibly! And then stared at the palm tree again.

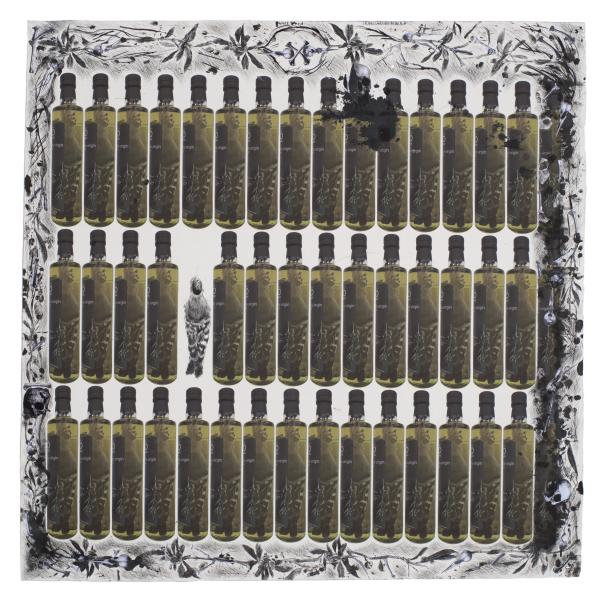

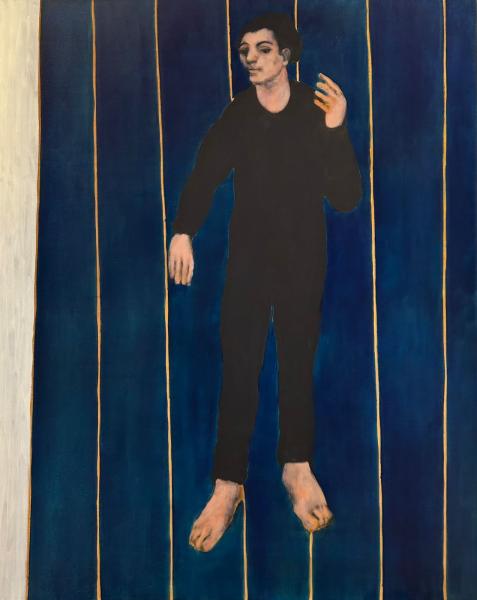

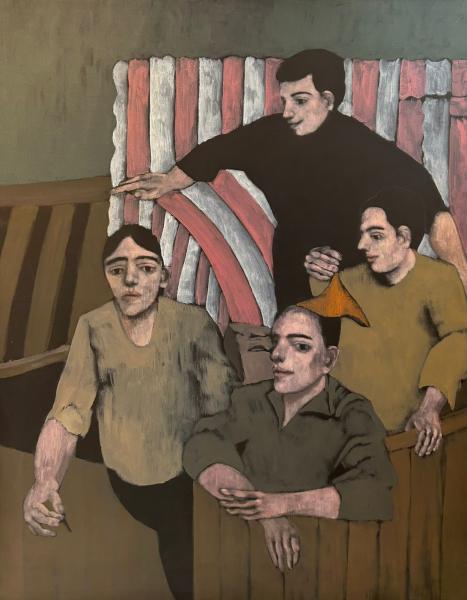

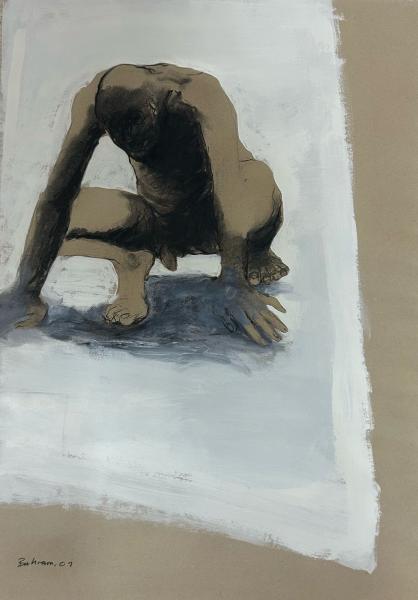

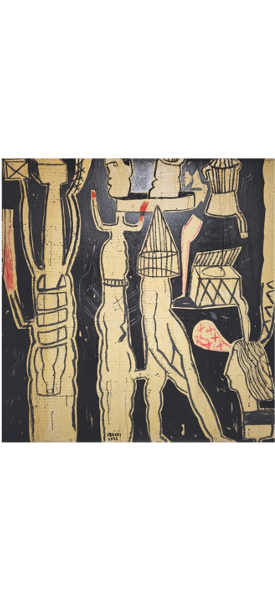

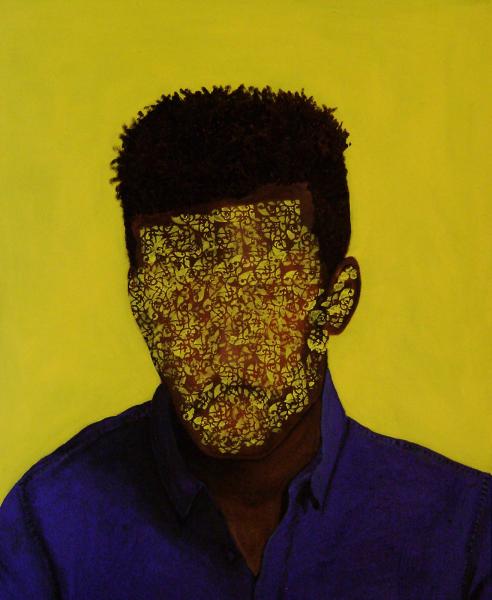

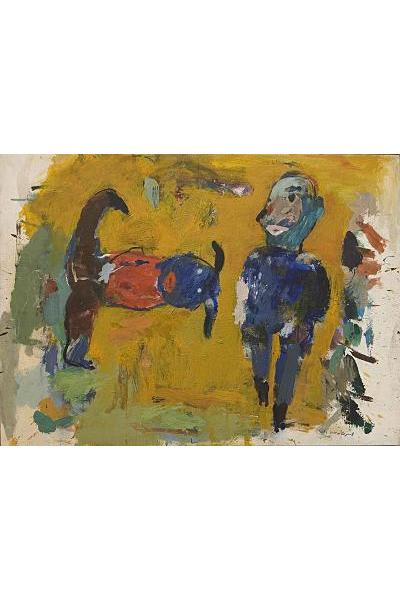

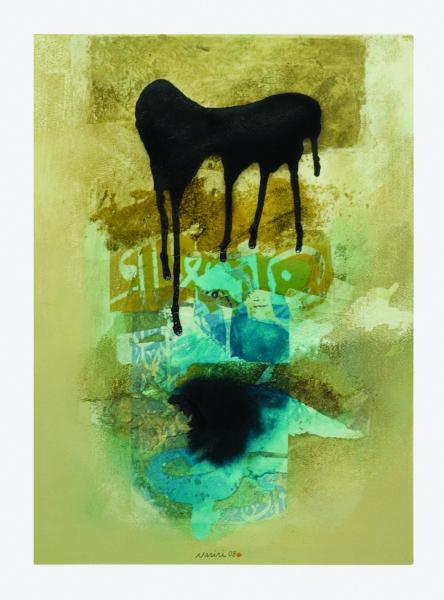

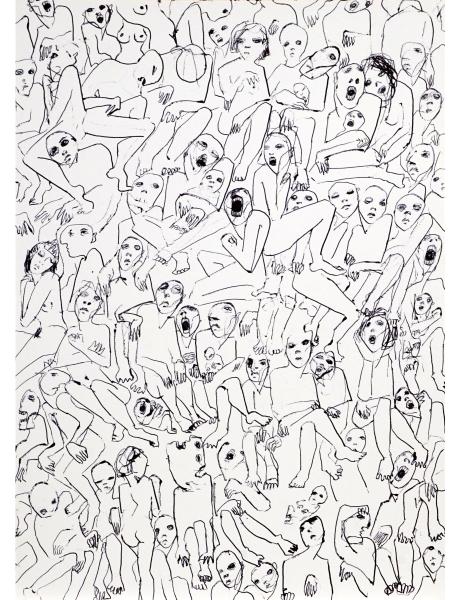

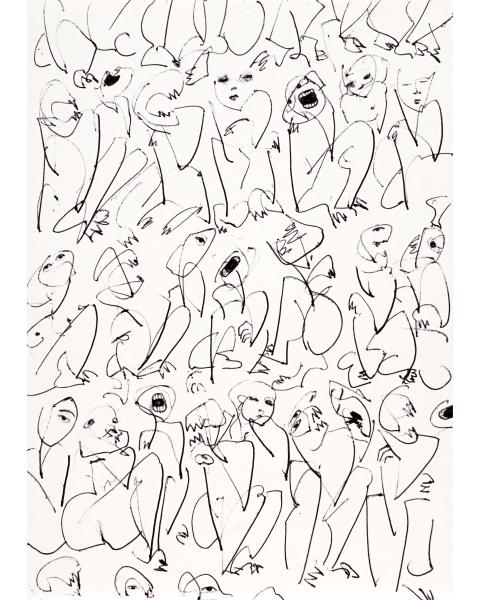

The word zeft is used in Palestine specifically, and the Arab region in general, as a contemptuous term expressing a wide range of emotions—from a discouraged state of mind to one of repulsion, and sometimes it points to bad luck or a way to describe an awful situation. This suited the concept of my series Standby (2008), which expressed the condition of the Palestinian people, who seemed to be dissolving in their waiting, as the 60th anniversary of the Nakba passed.

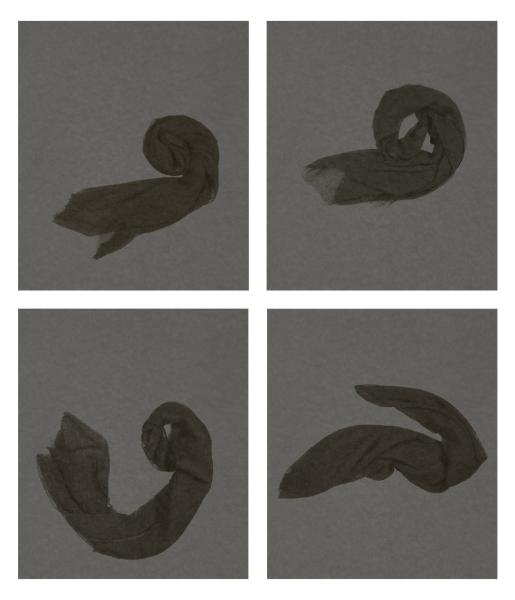

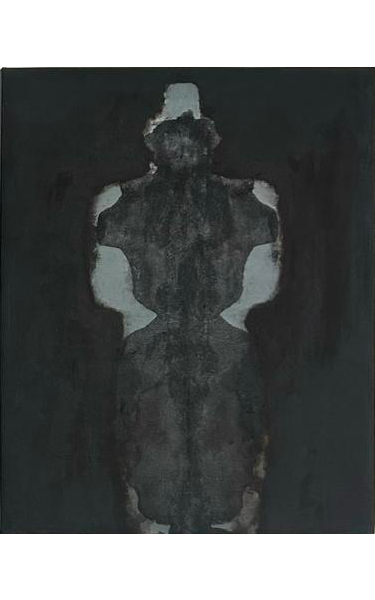

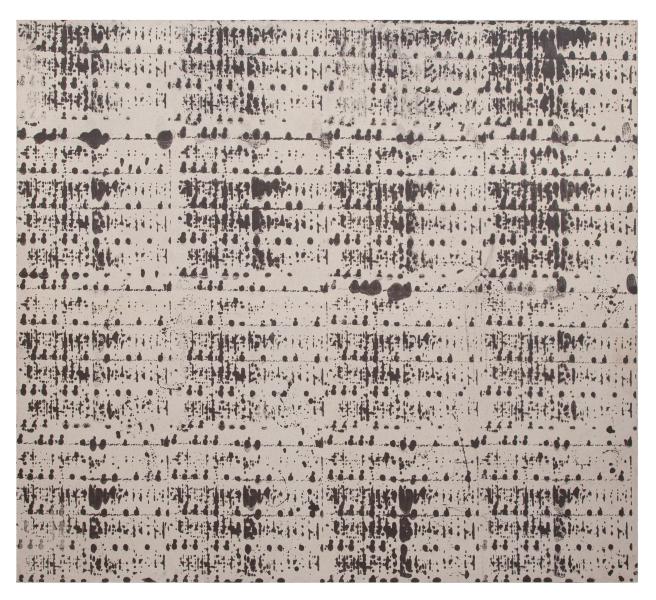

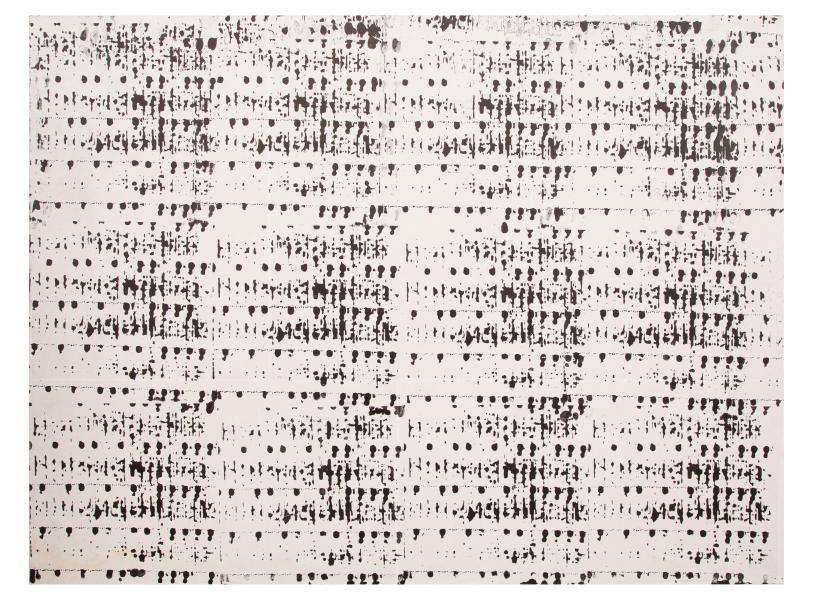

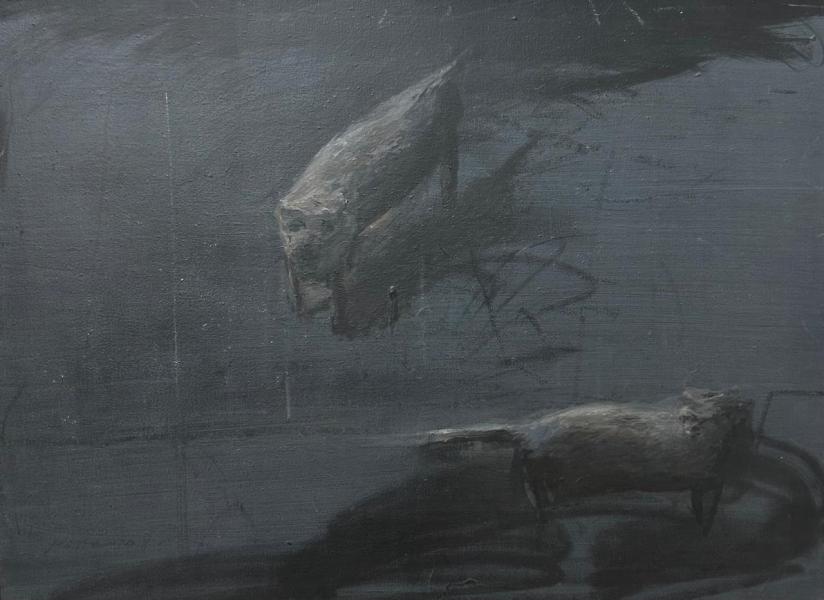

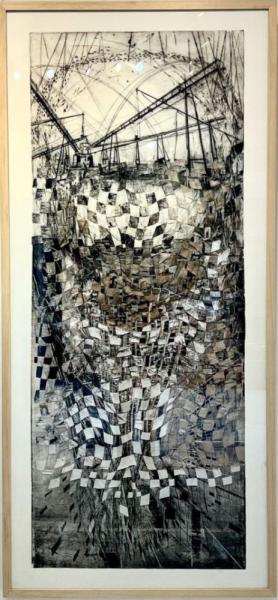

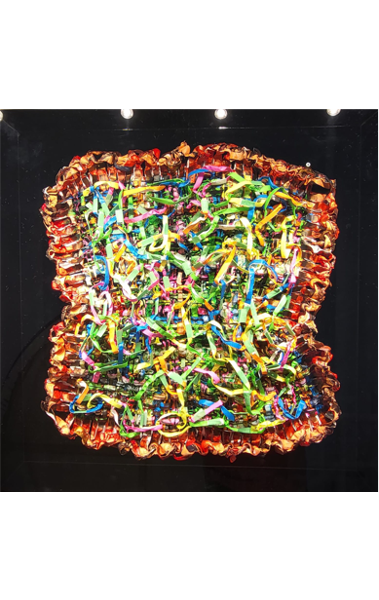

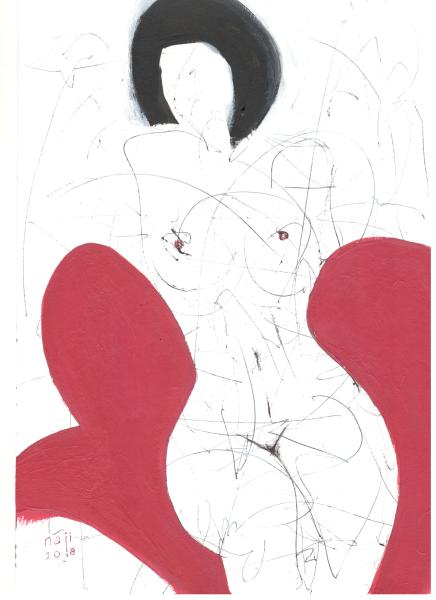

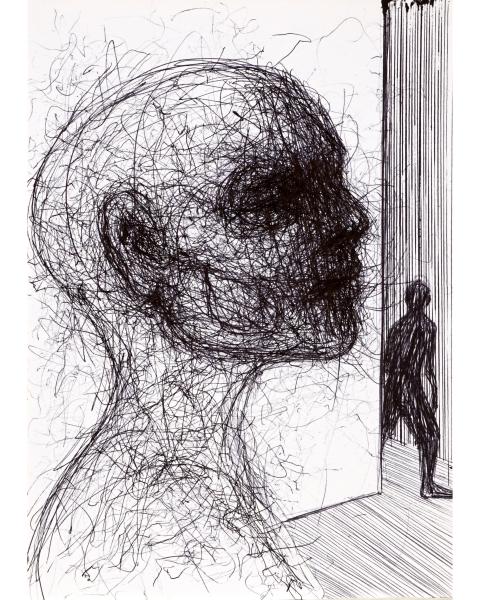

The first time I started using zeft as a raw material in my work was in Standby. I started making it out of a passion for discovering new materials, sometimes mixing it with henna and dyes, and to explore the meaning of the word zeft. I can confess, the material defeated me. After Standby I felt I had no control of it, and further to that, it controlled the other materials with its singular color, its consistency and shape. But I continued using it in limited quantities, as the color black, attempting to control it through continuous research and the addition of other mediums.

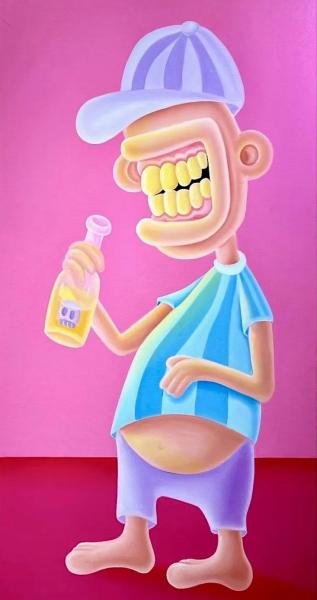

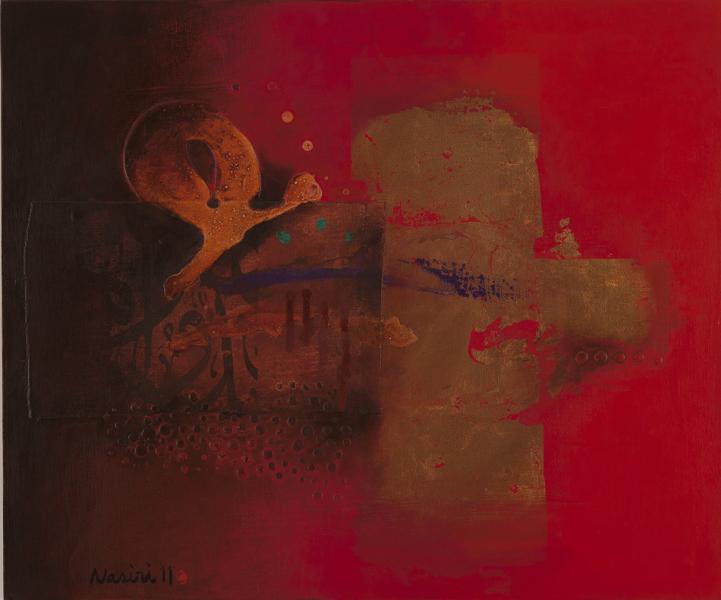

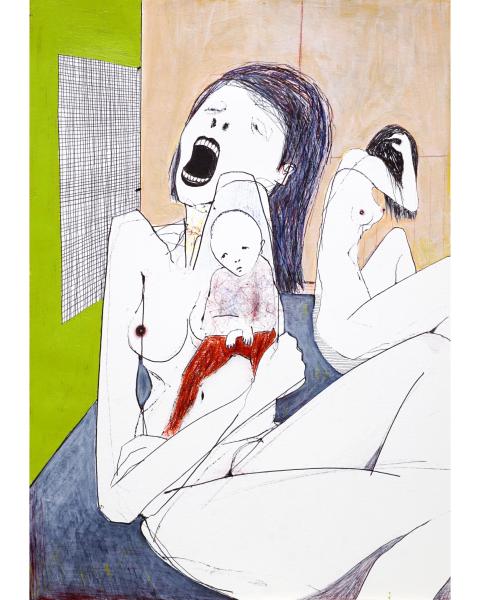

Later when I was working on Low Quality Love (2015) I overused zeft, and I achieved new, exciting technical results. This enticed me to go back and obsessively interact with the material again, except this time the research led me in another direction, to understand it in its chemical form. I worked with a chemist friend of mine in a university lab in France to analyze all my tests since 2008 and we discovered the mistakes I had made in controlling the temperature and timing the mixing and application of it on the canvas. This helped me to achieve forms outside the laws of coincidence that had been governing me.

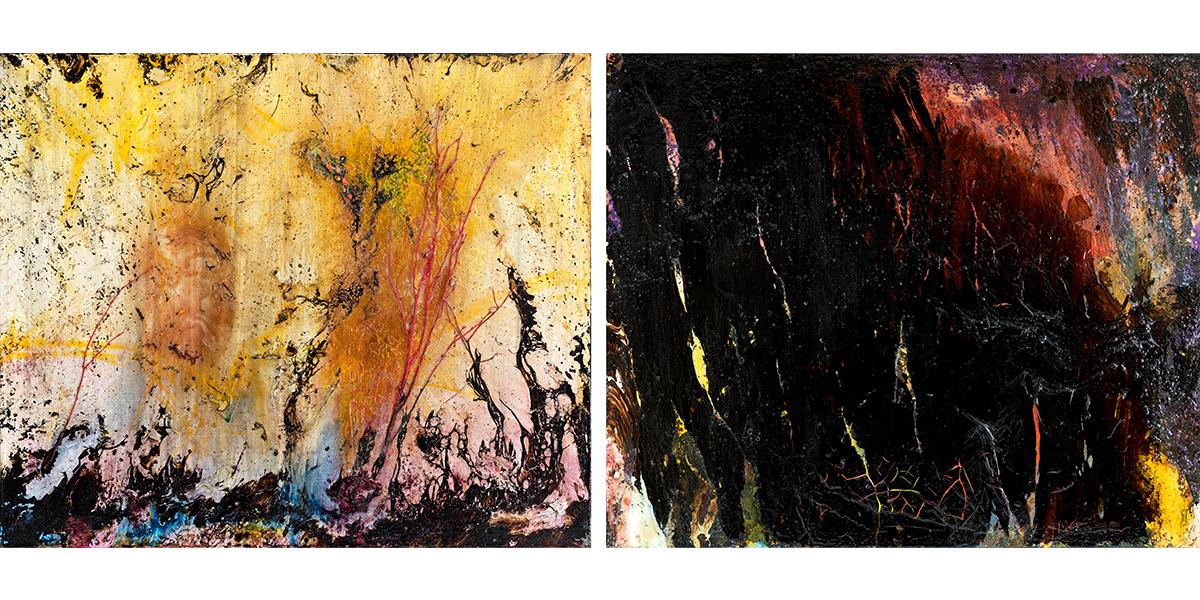

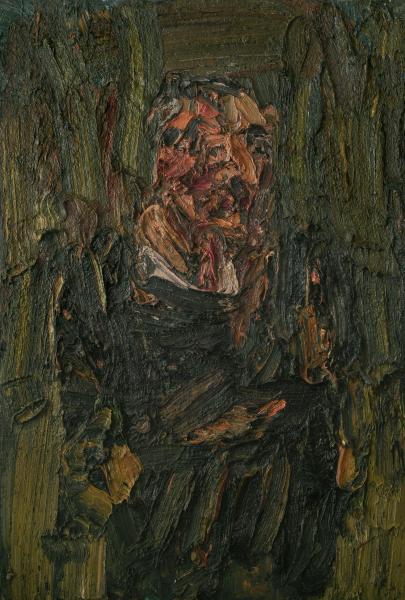

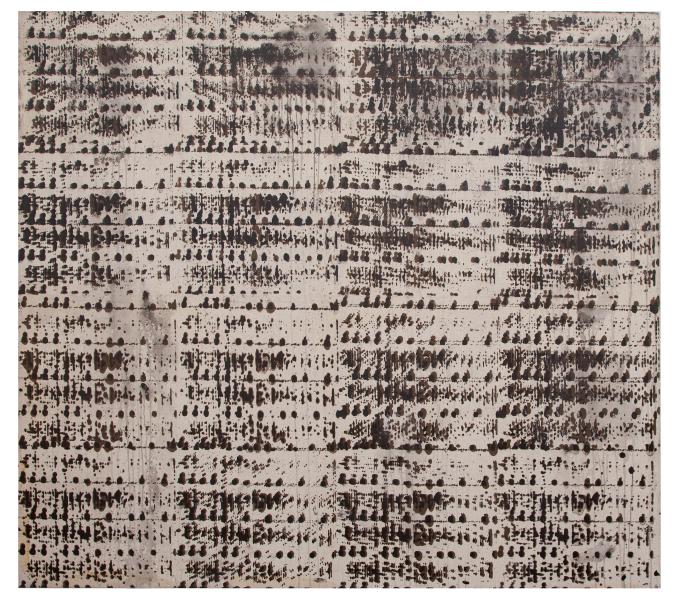

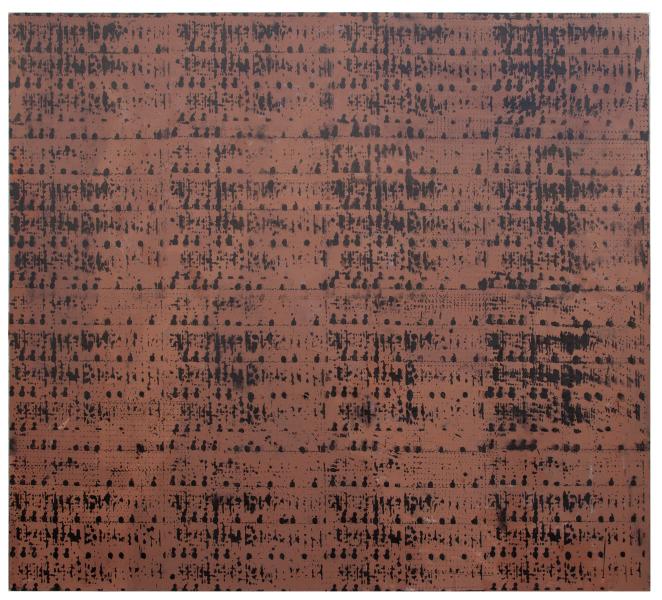

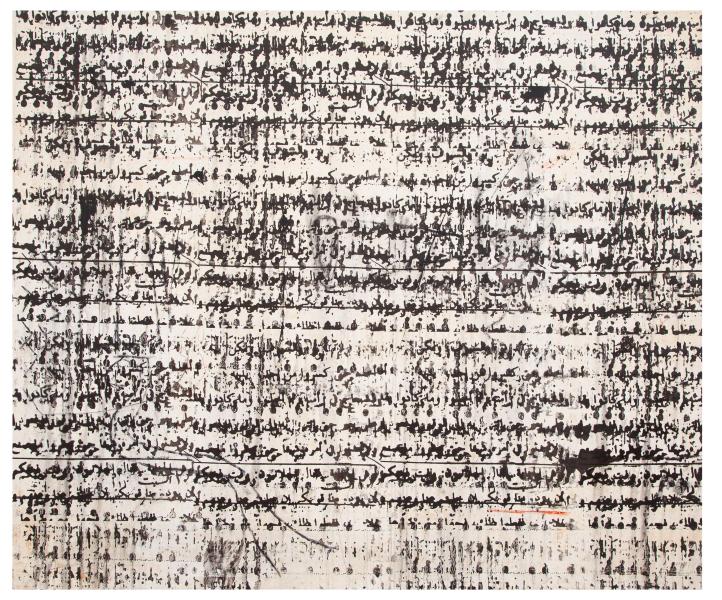

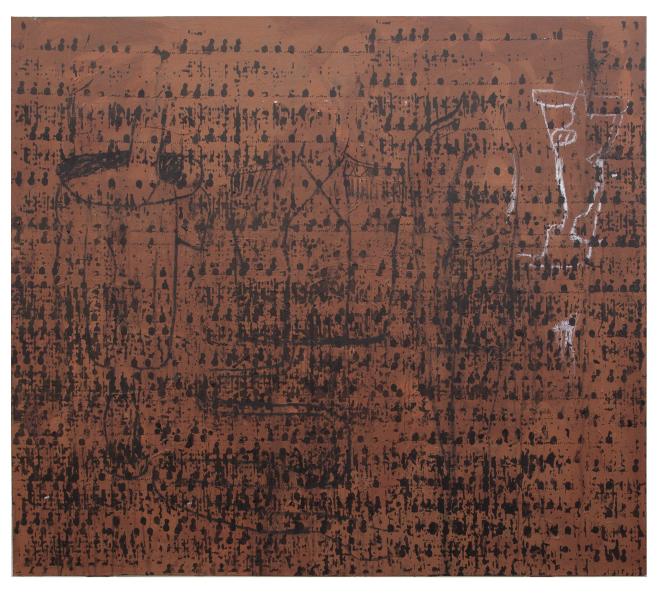

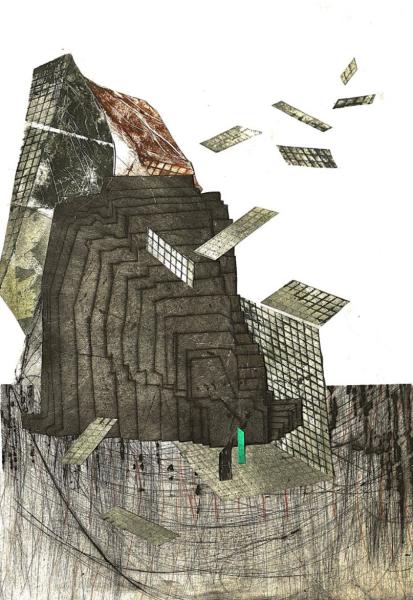

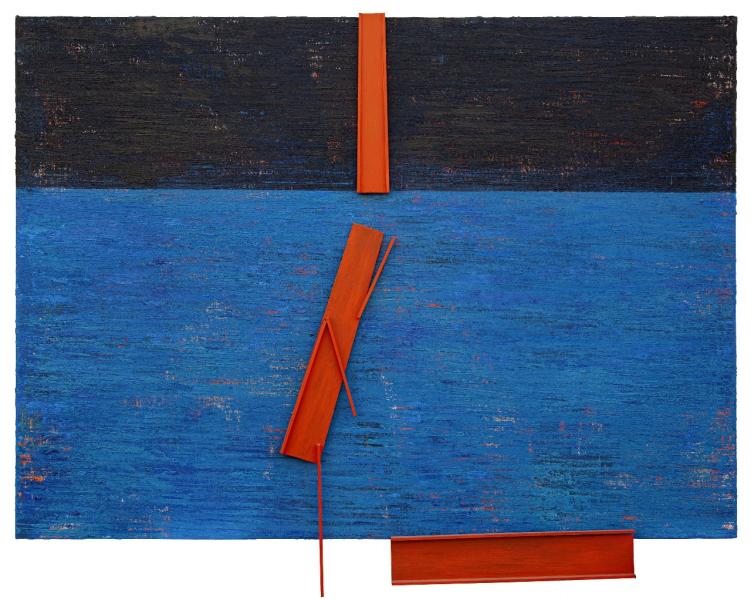

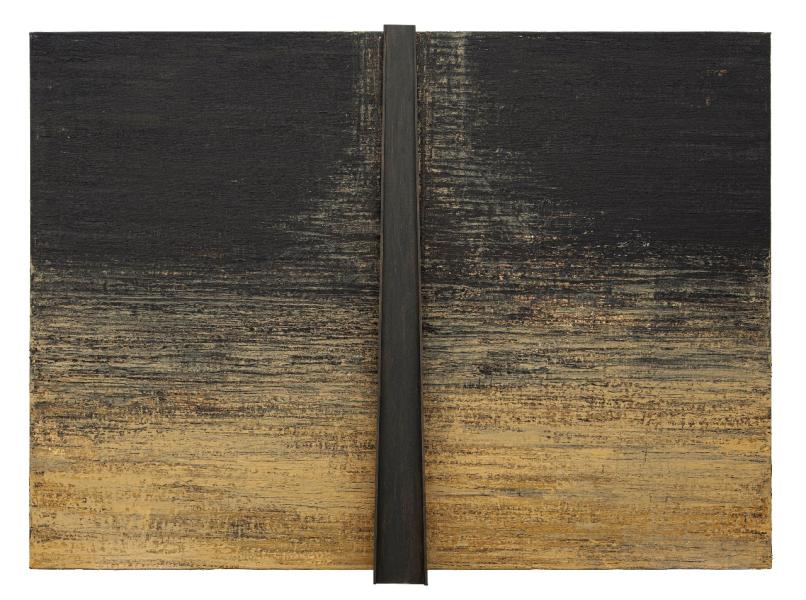

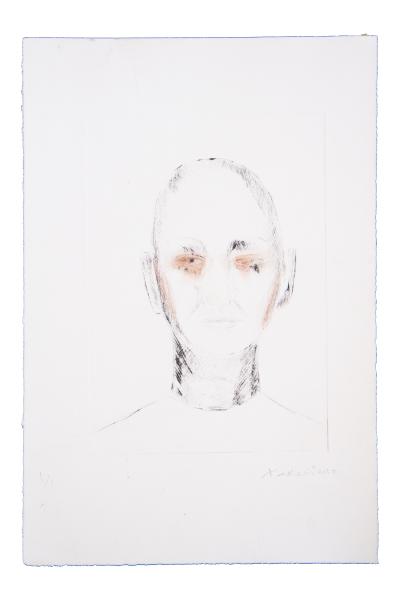

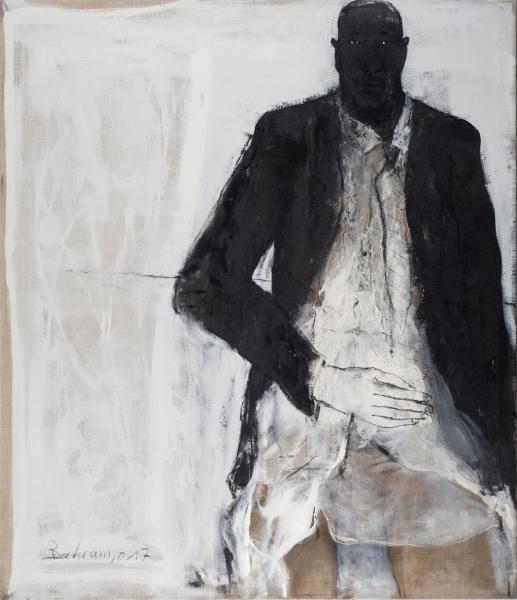

Zeft (2016-2017)

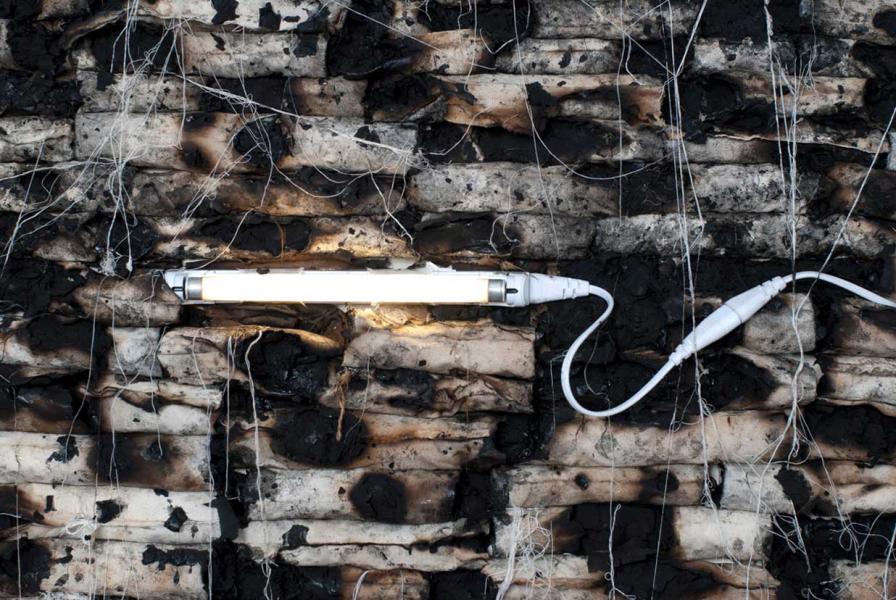

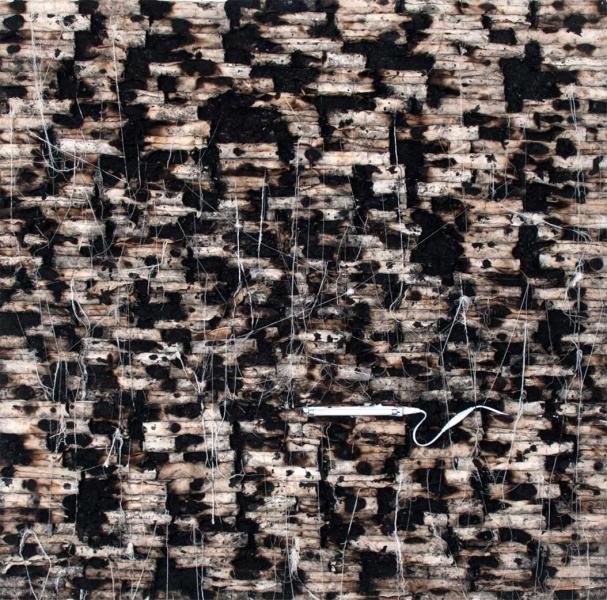

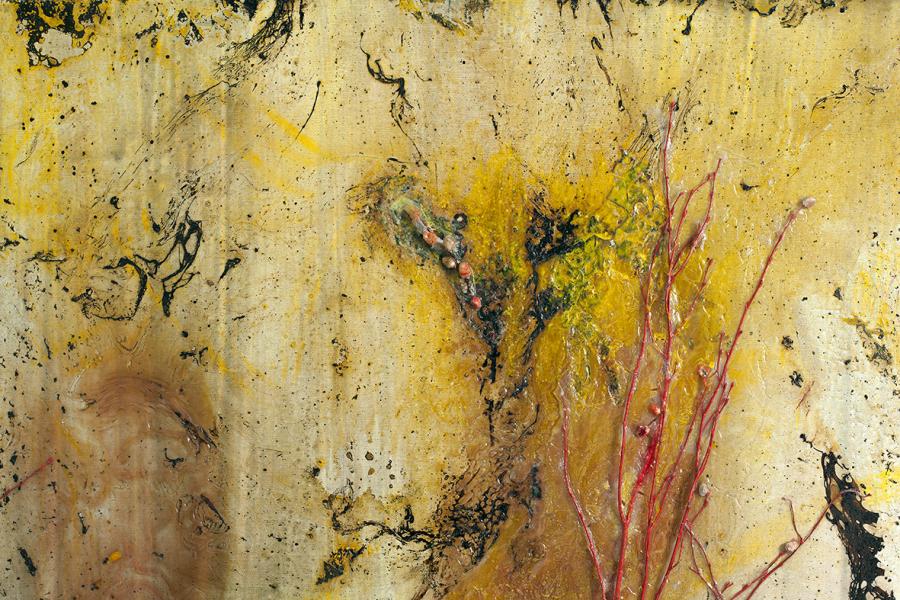

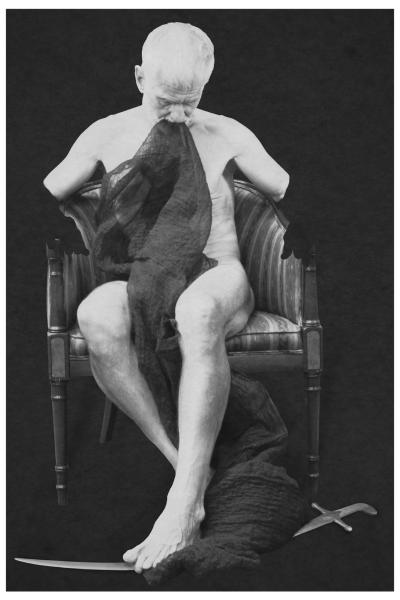

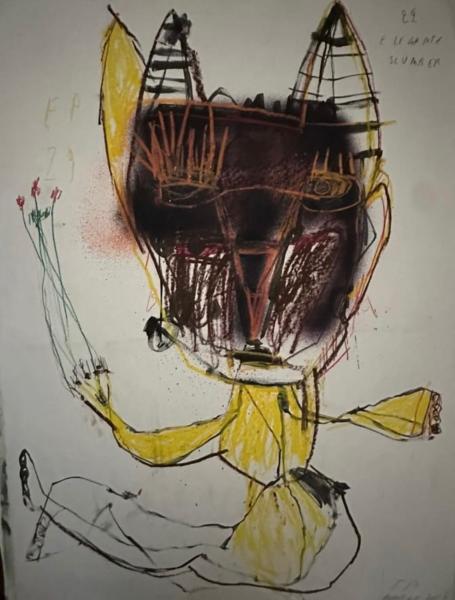

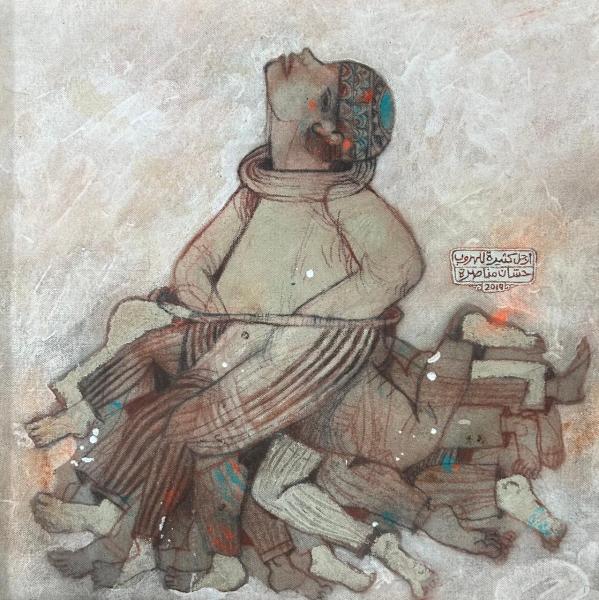

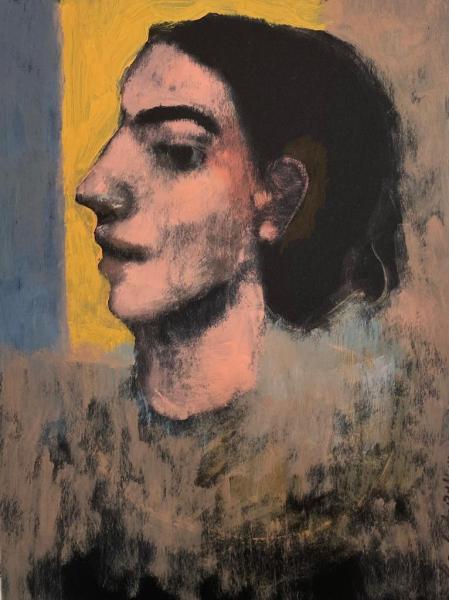

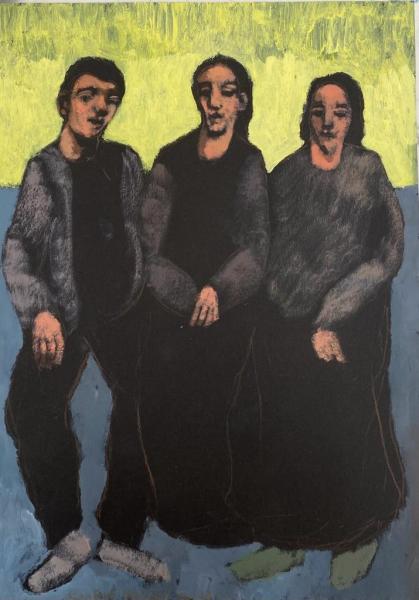

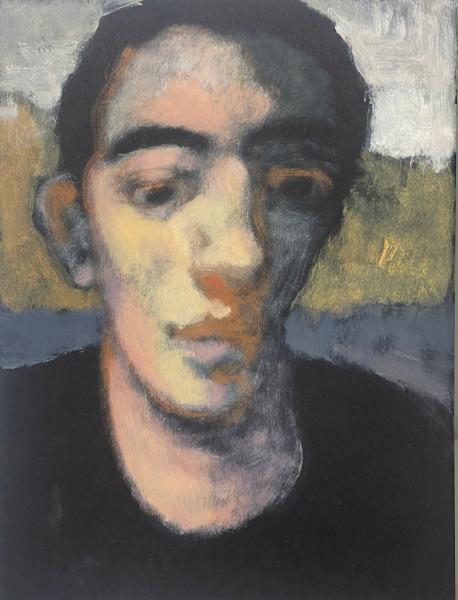

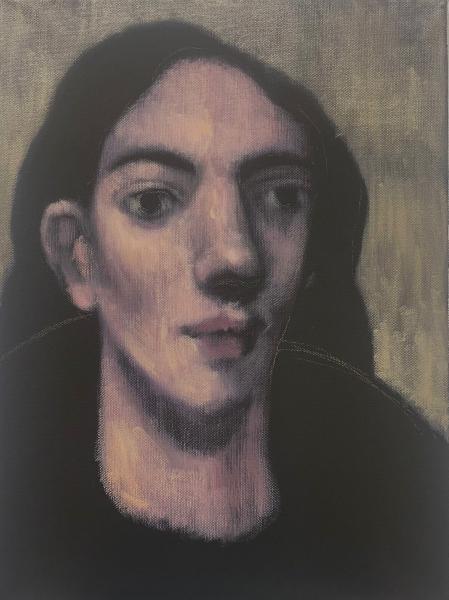

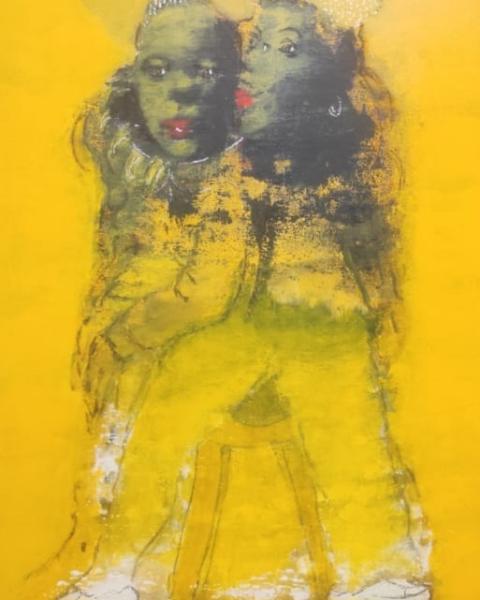

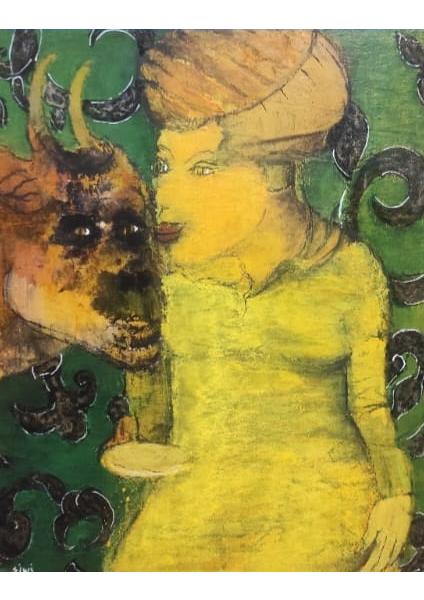

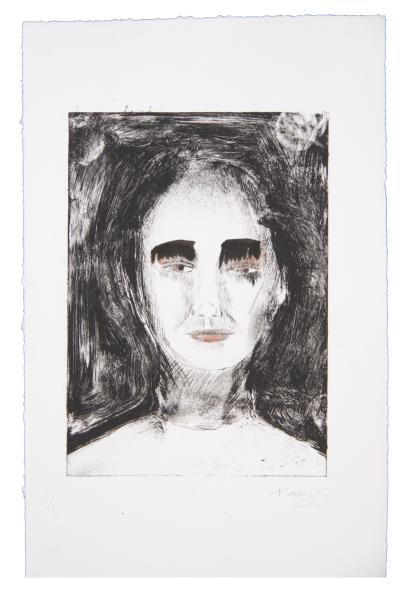

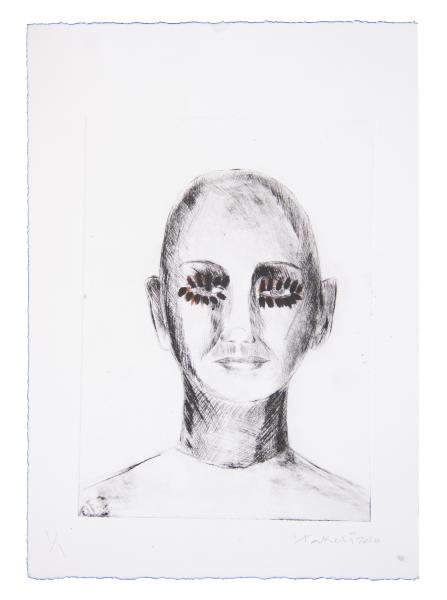

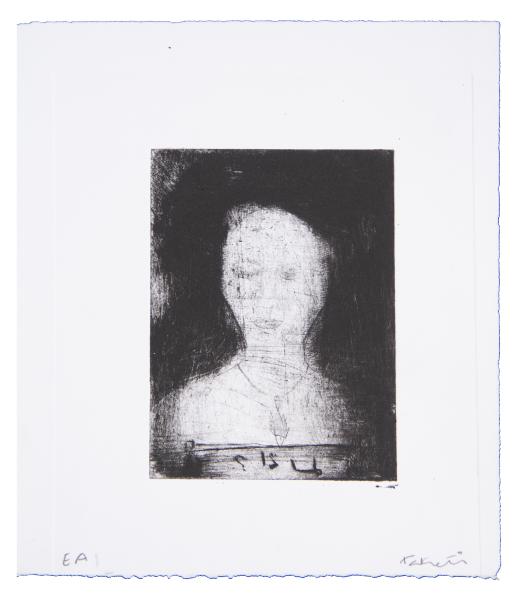

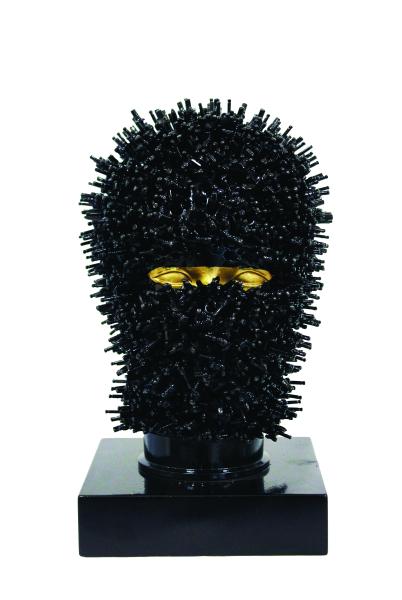

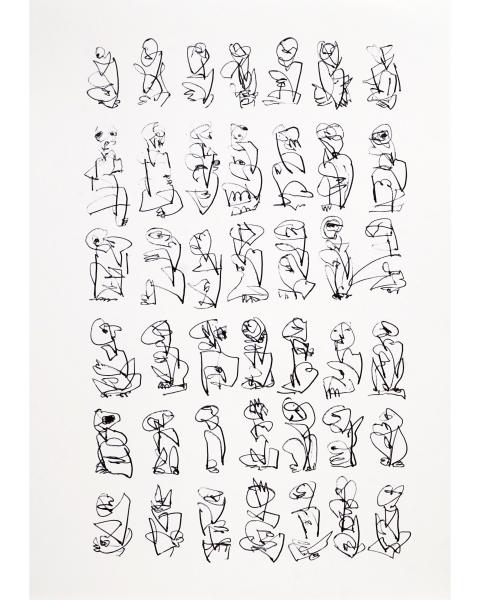

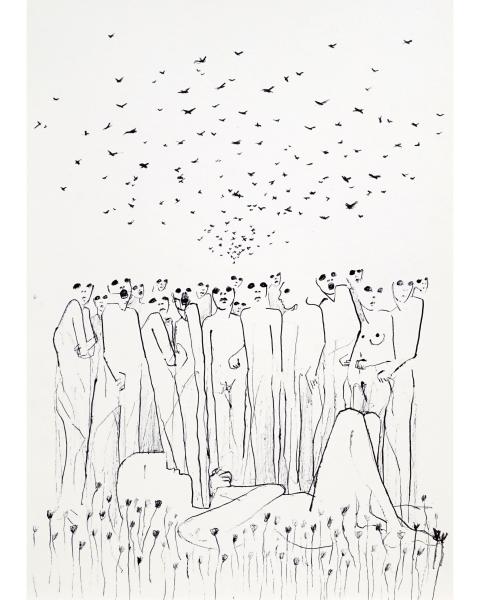

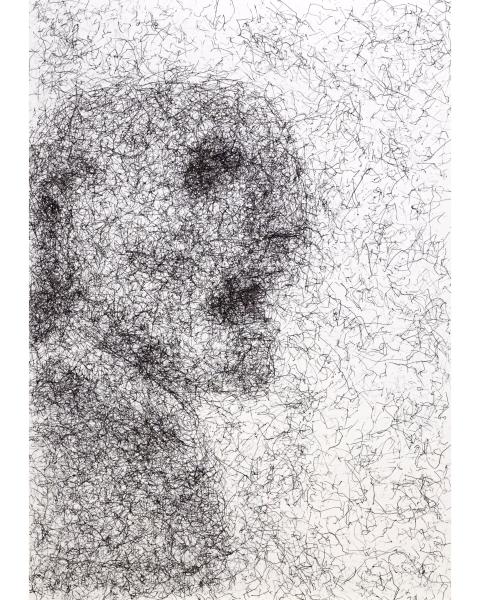

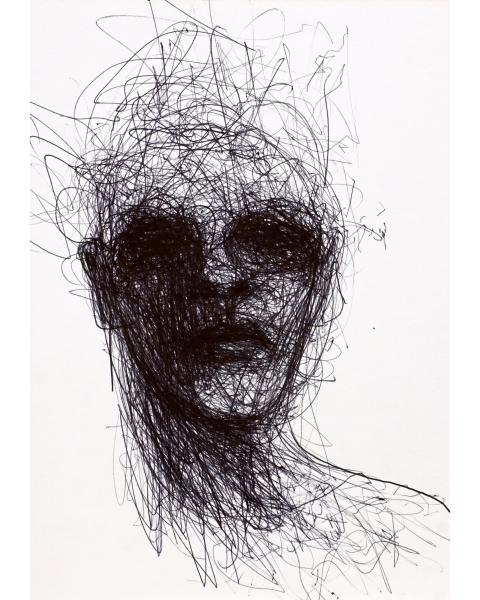

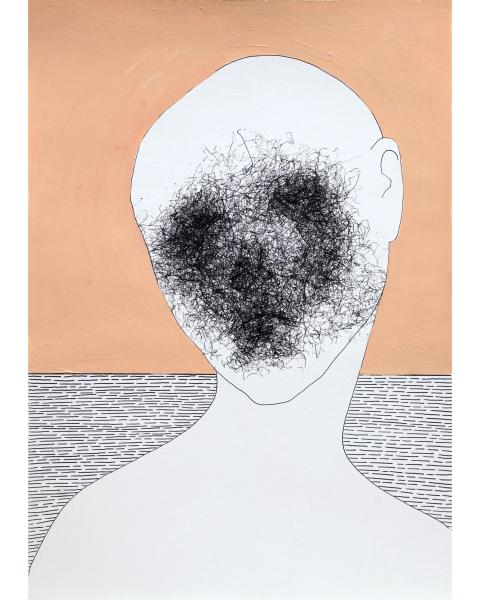

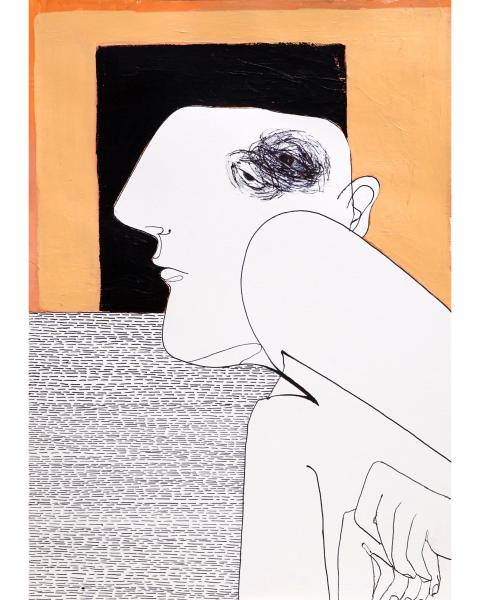

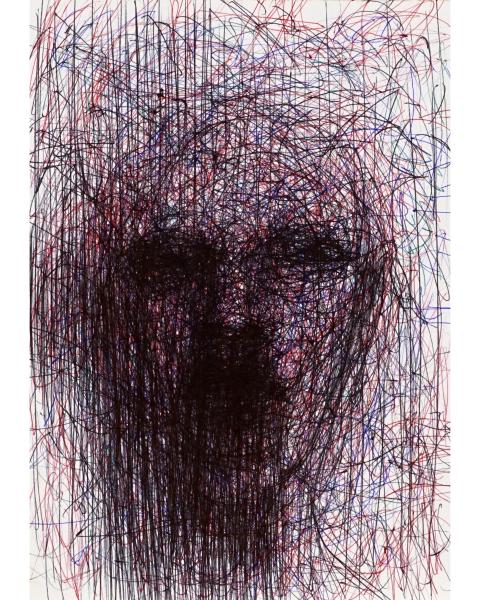

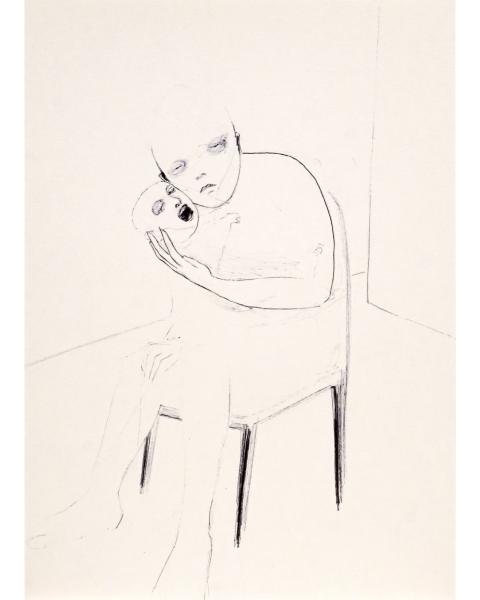

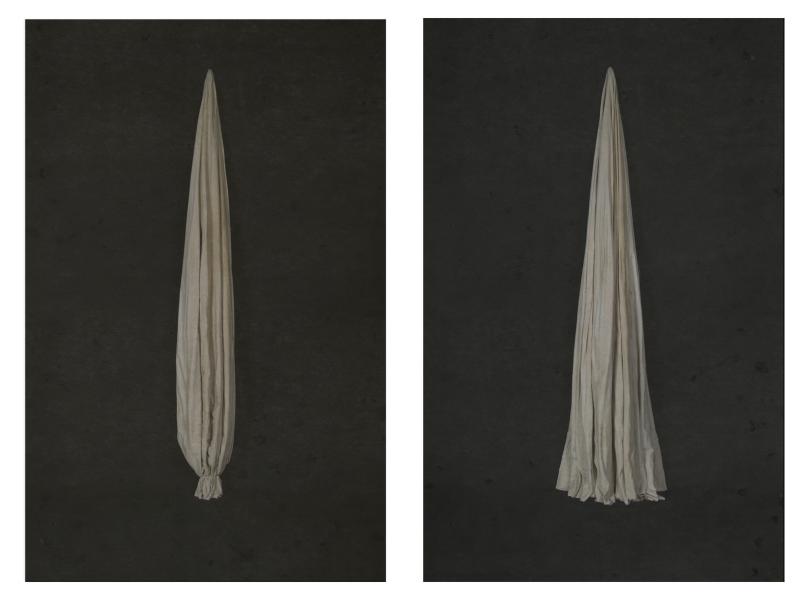

From that point on I set forth extensively researching and interacting with the material once again in Zeft (2016-2017), approaching the human form, and particularly the face, as I had in Standby. For the first time I worked at a smaller scale to better control the forms and got rid of traditional tools for painting, replacing them with iron, wood and plastic, using different gestures. I controlled the temperature, cutting and working with the material at specific time intervals to create the layers. Never before had I reused the zeft that had dripped onto the studio floor, but after it dried I scraped it up and applied it, in new layers. From there I got the idea for my next series.

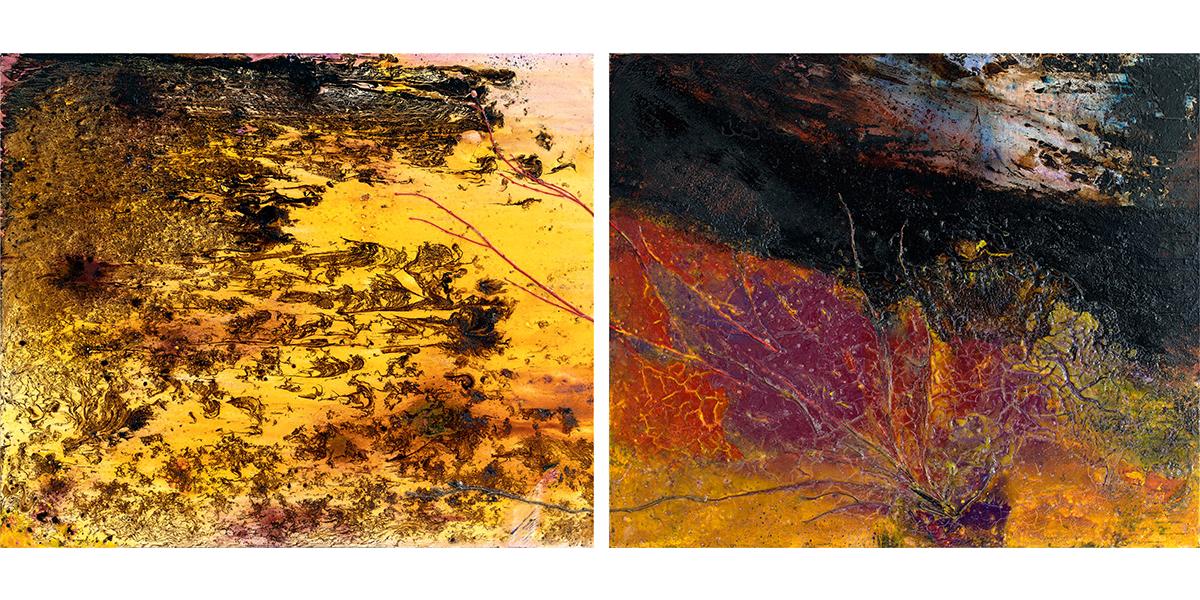

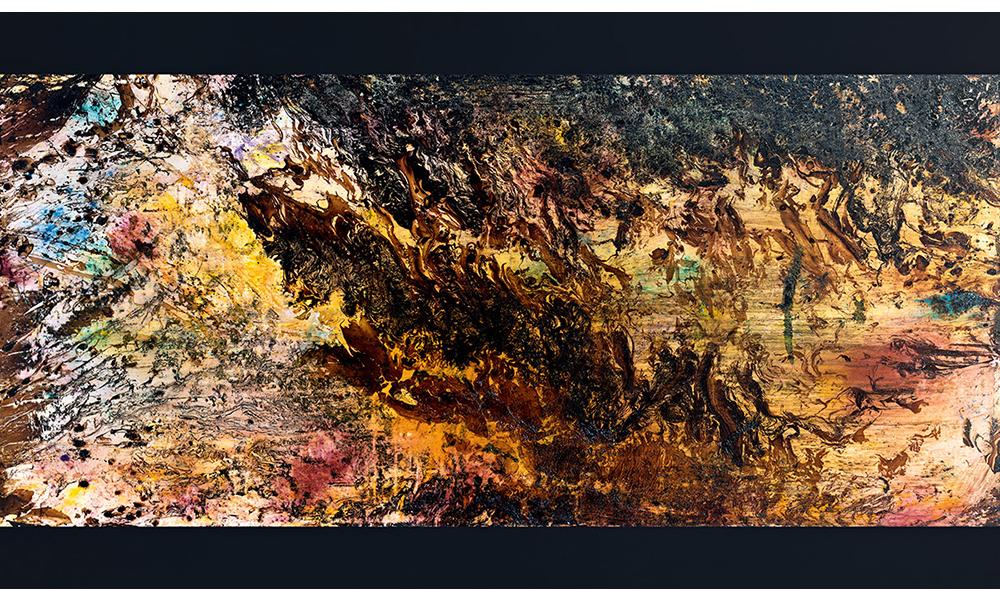

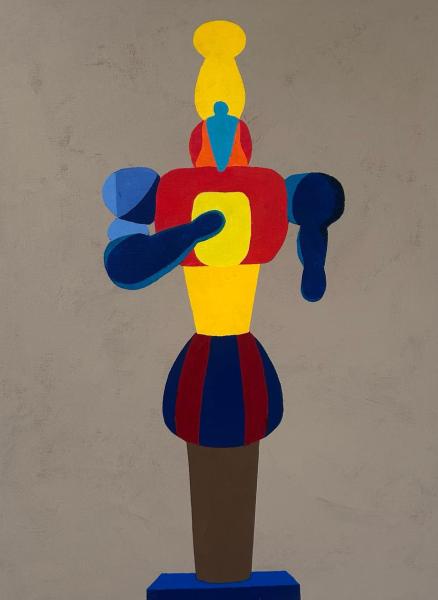

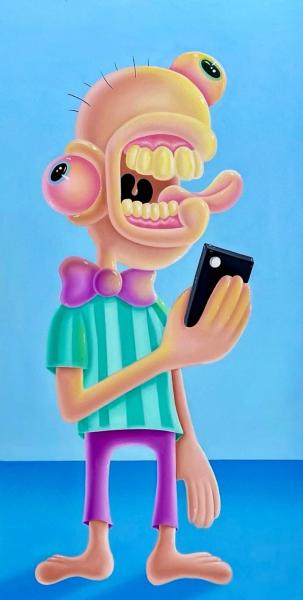

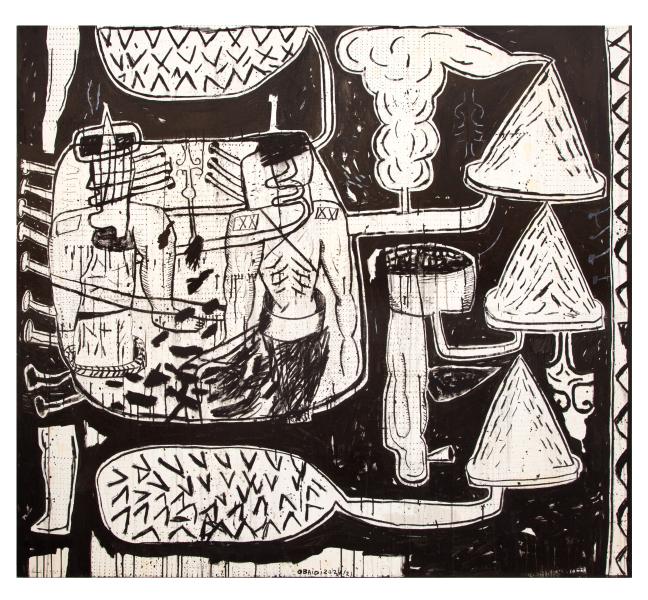

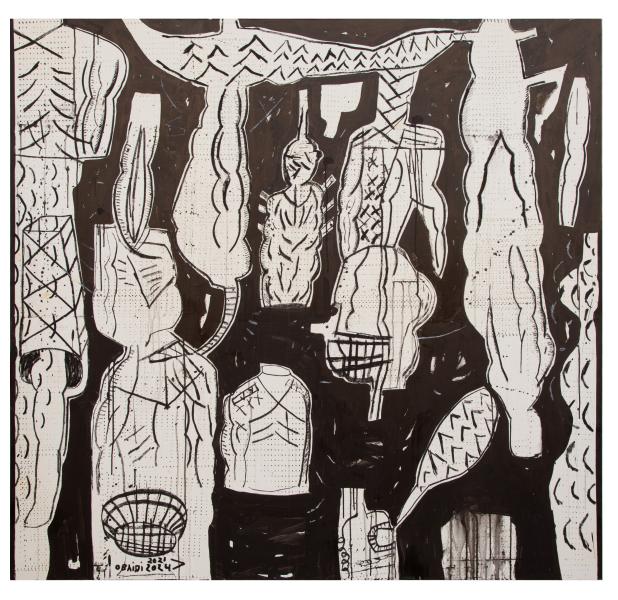

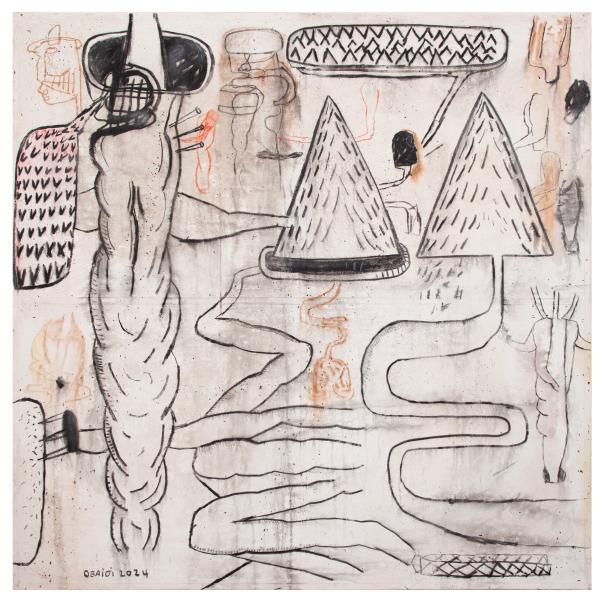

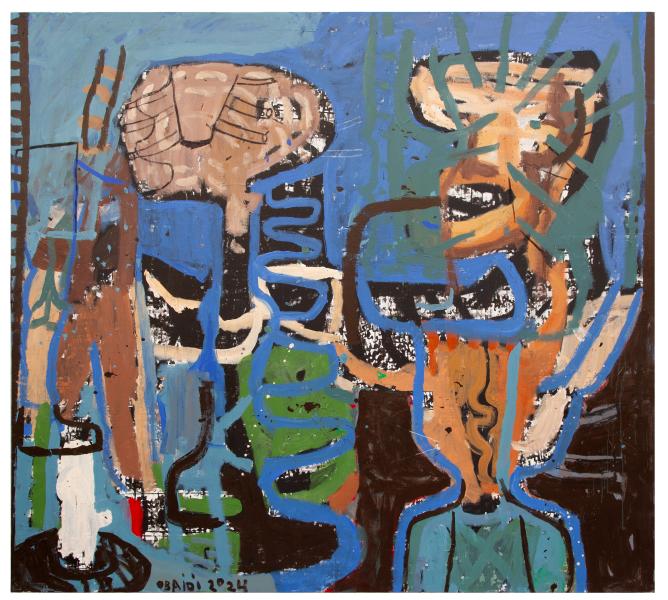

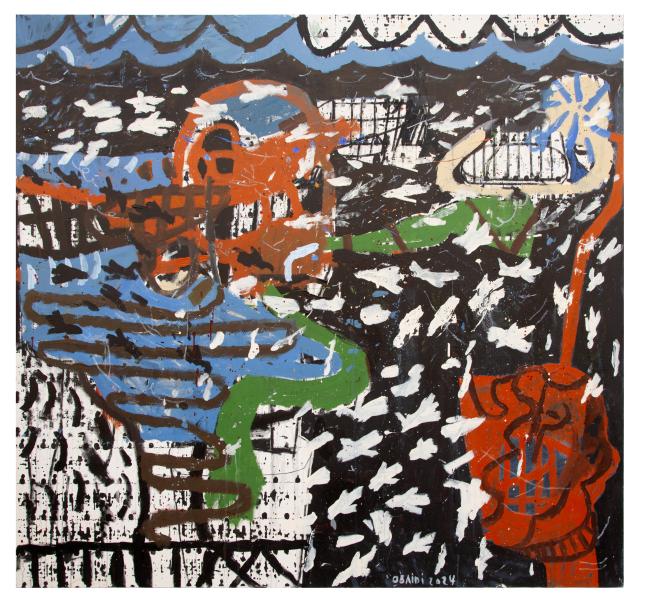

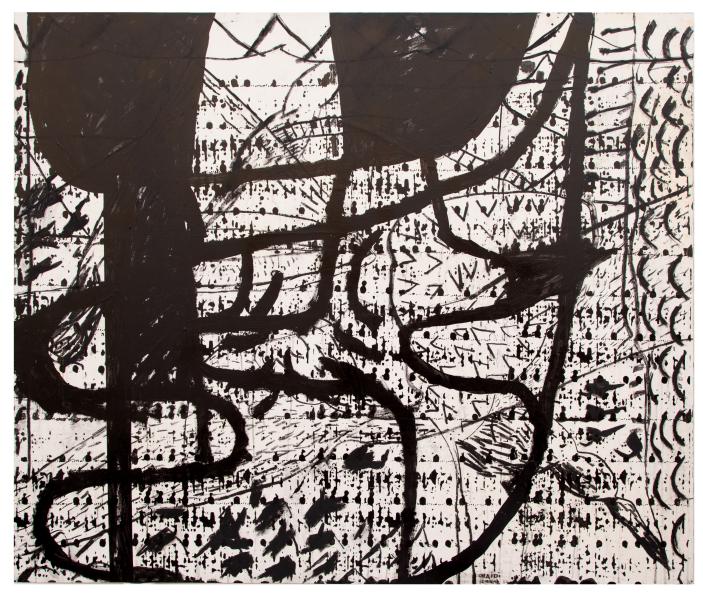

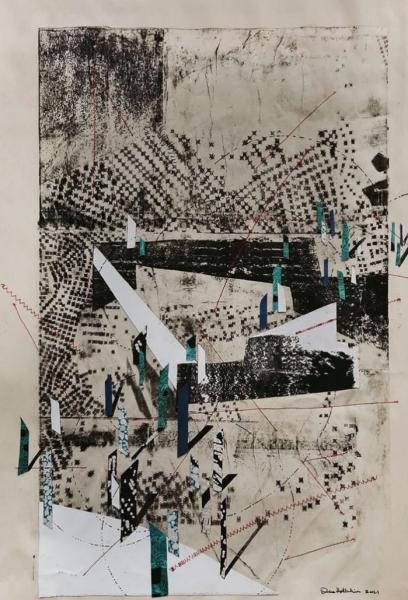

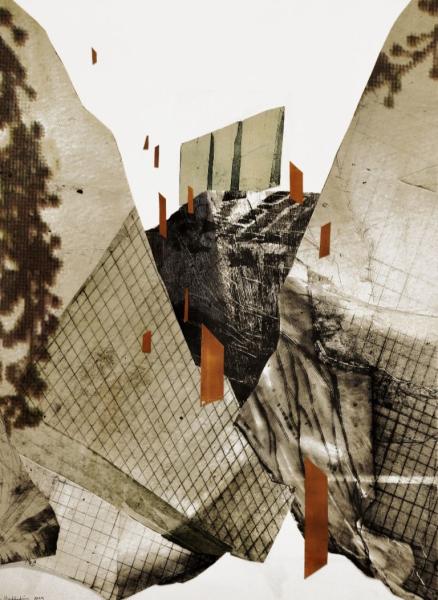

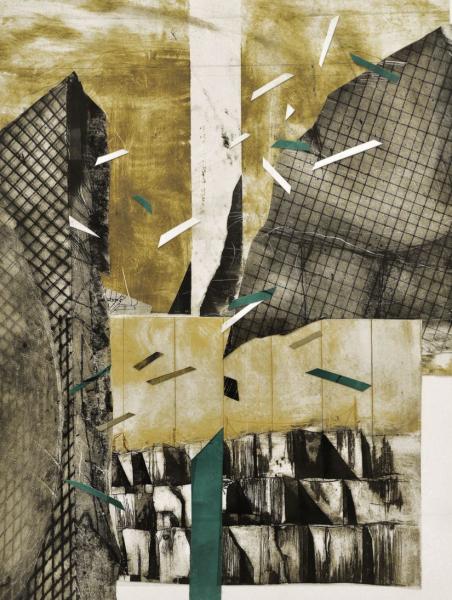

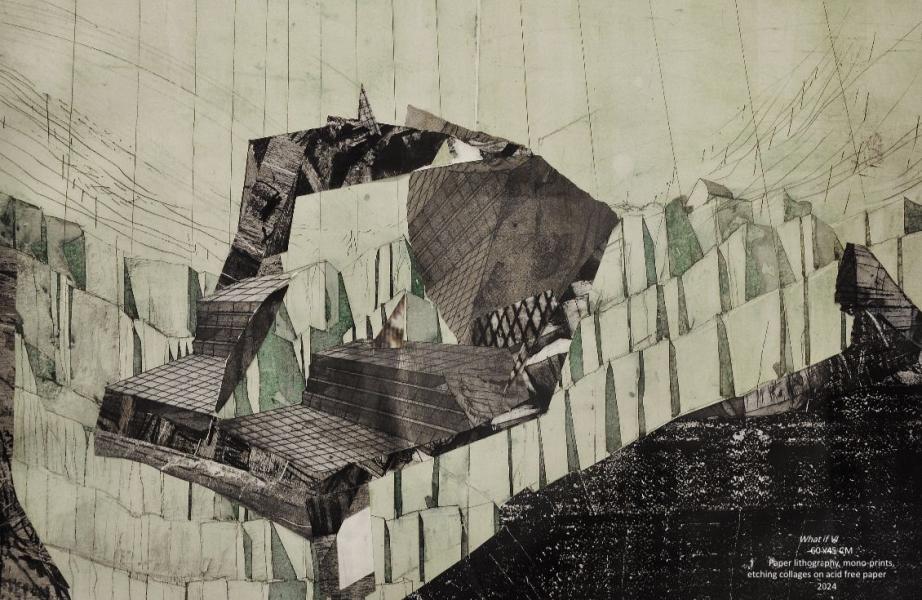

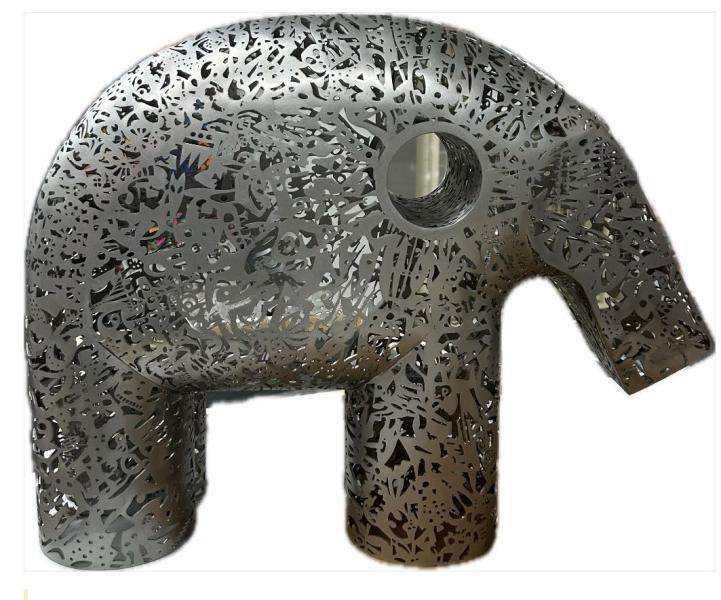

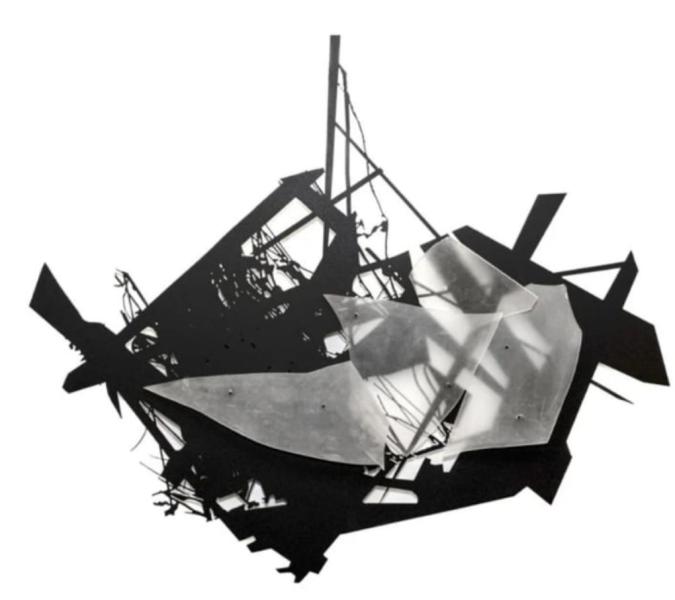

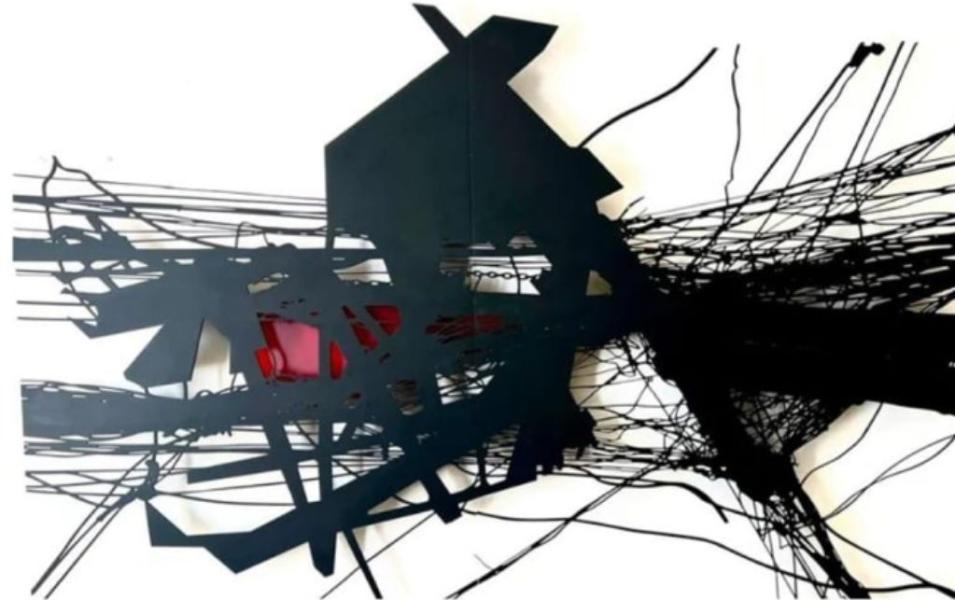

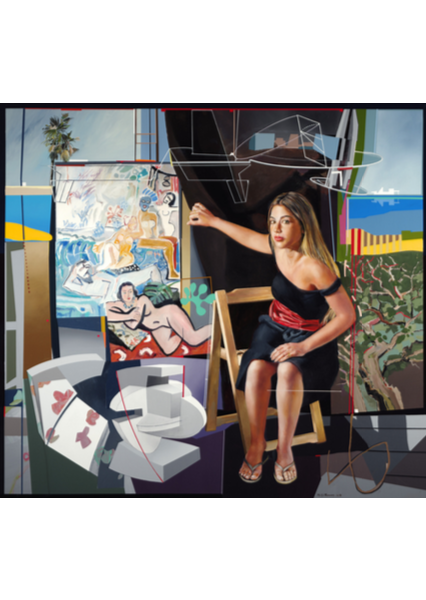

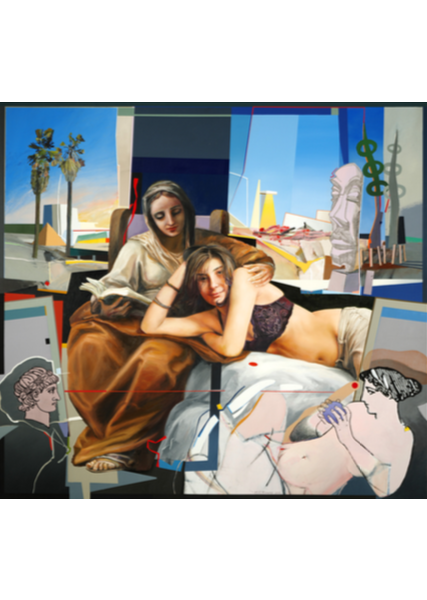

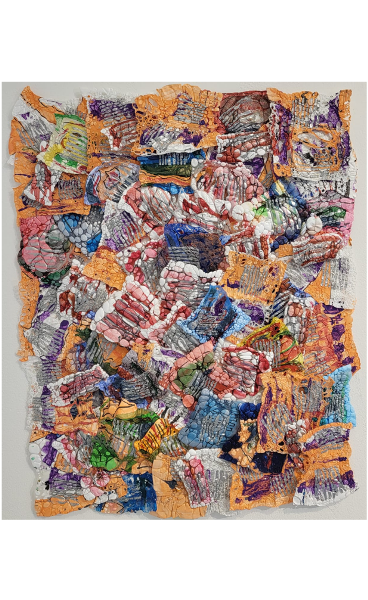

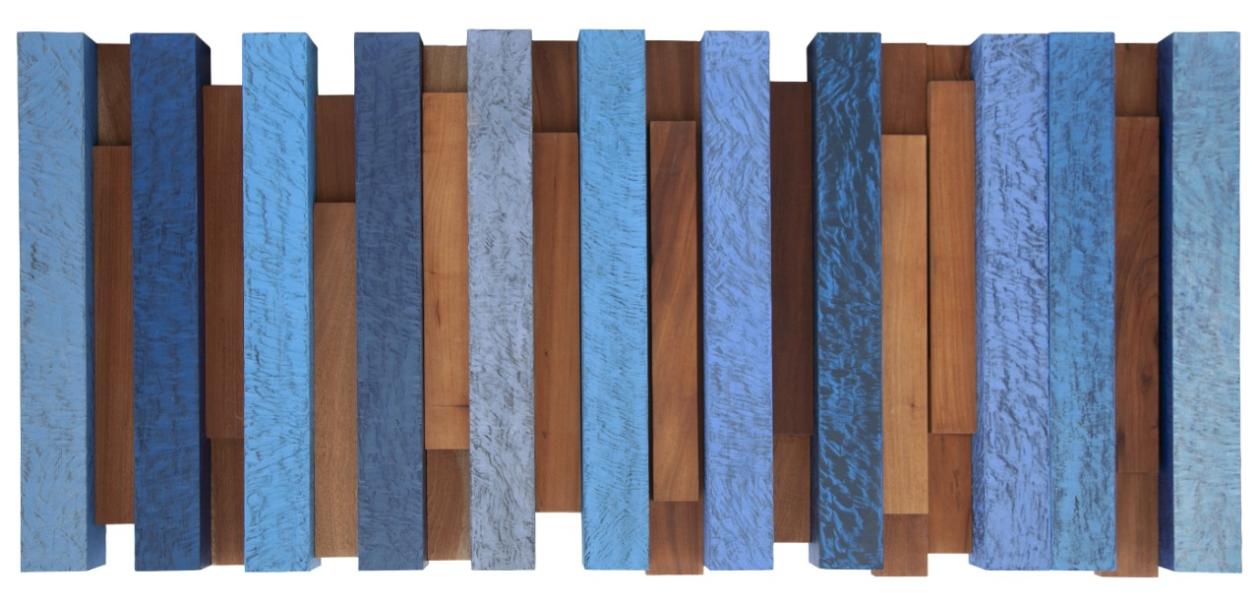

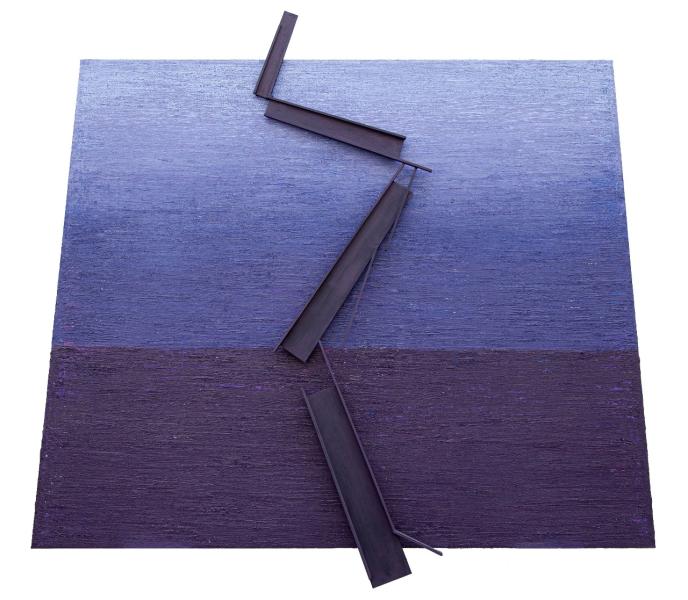

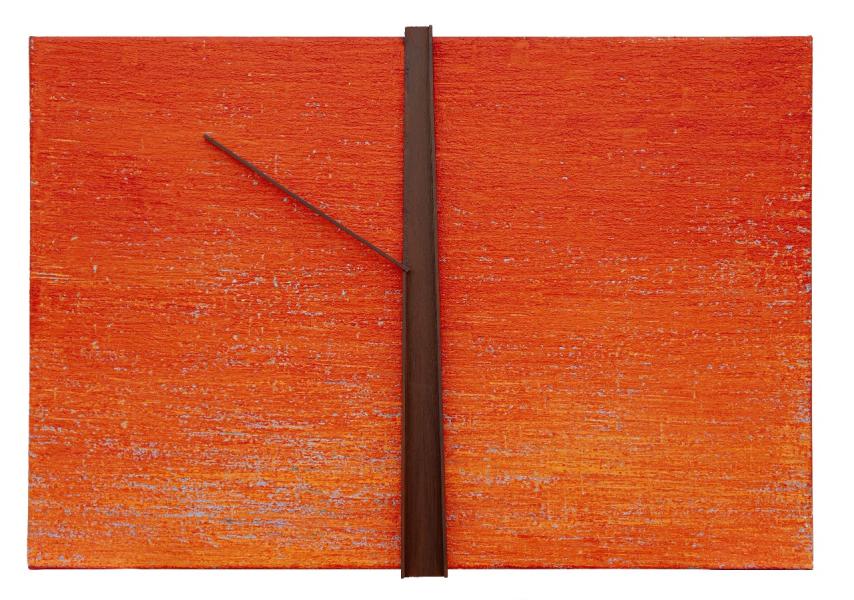

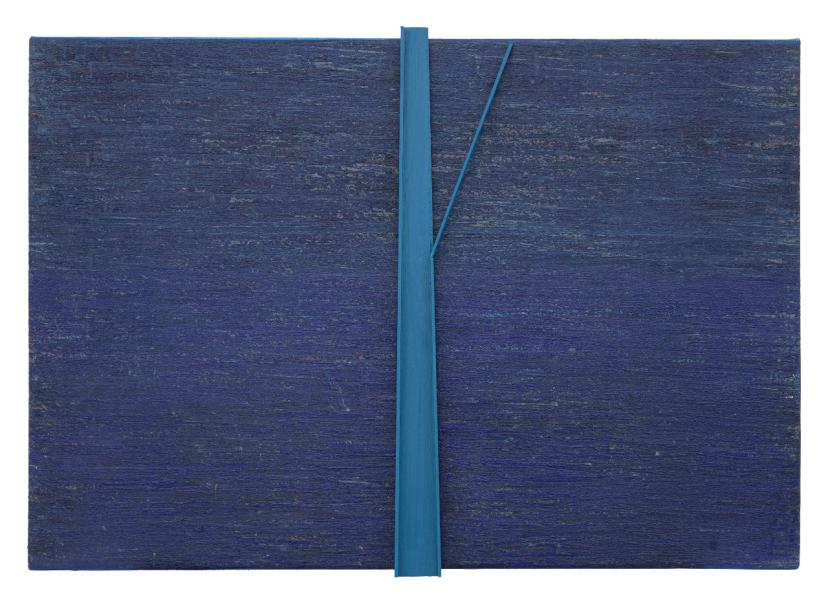

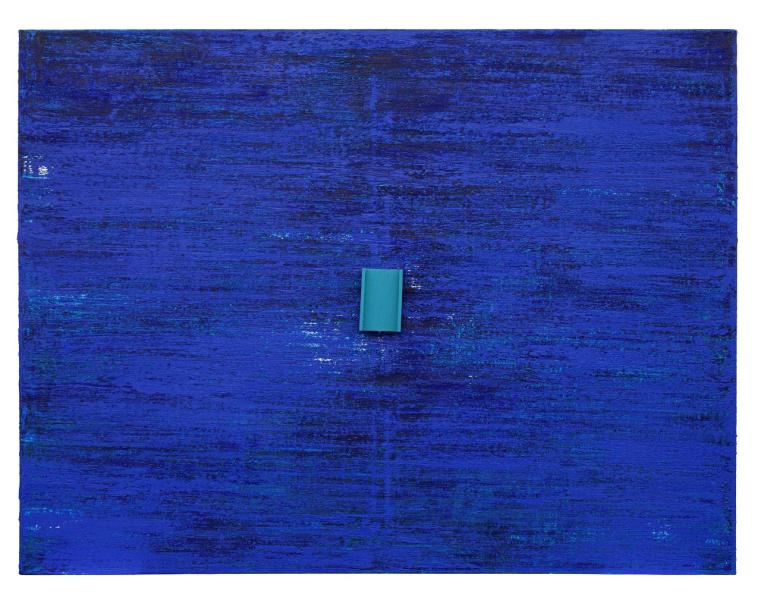

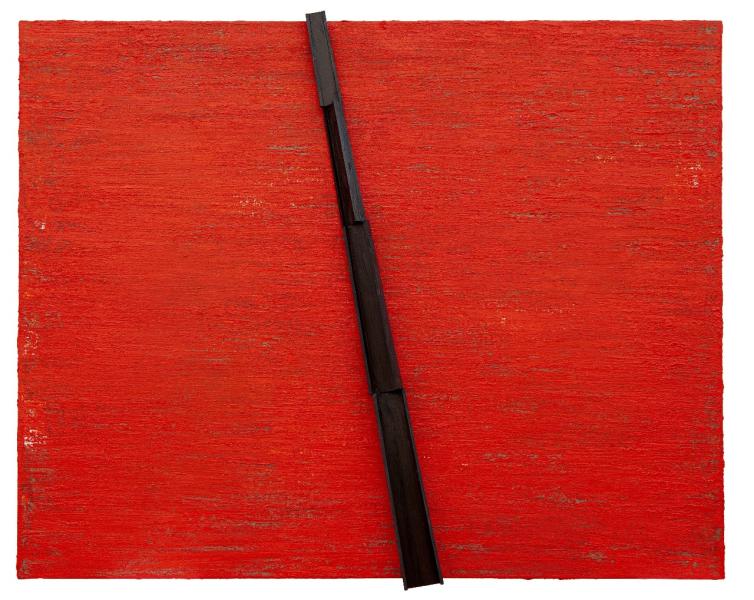

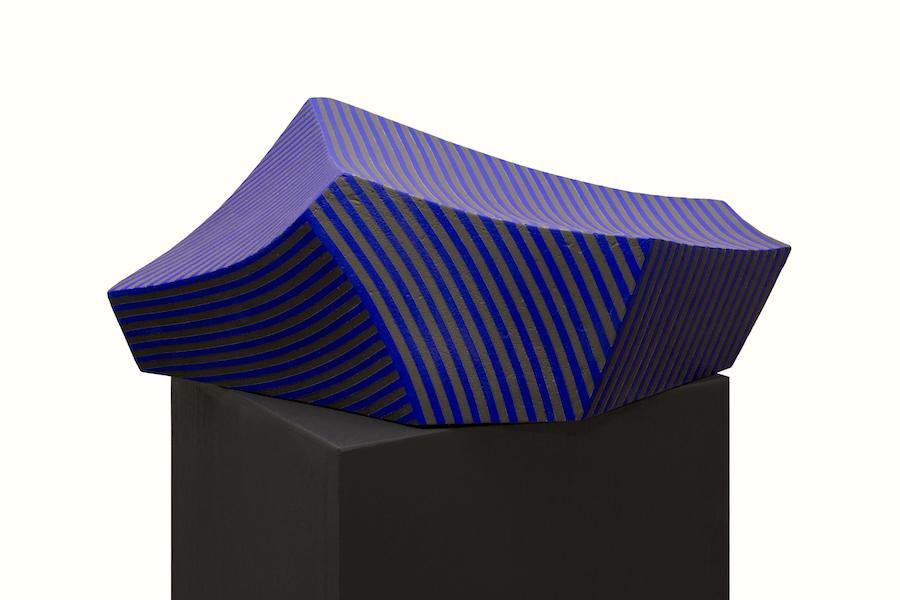

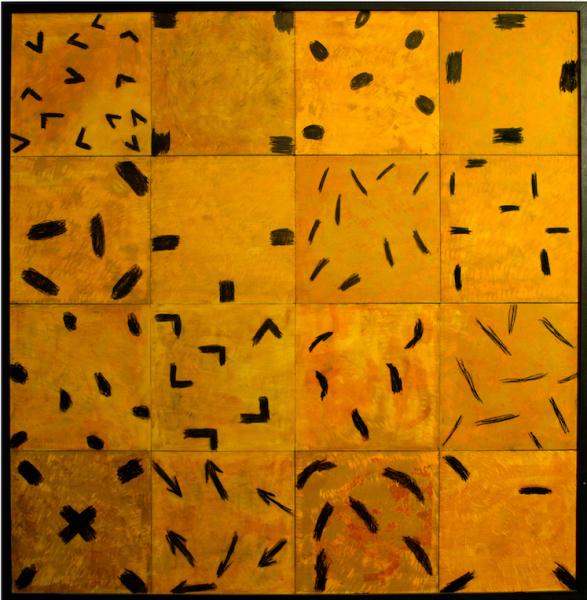

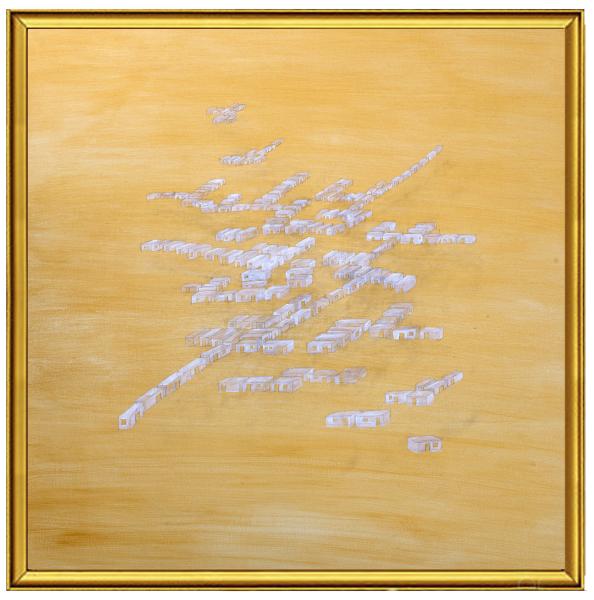

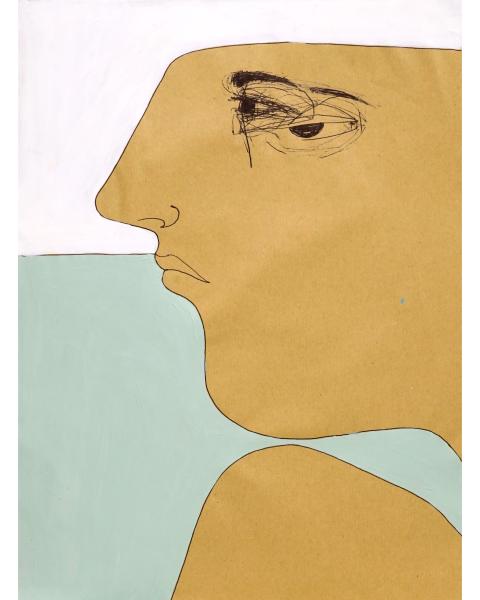

ZeftLand (2018-2019)

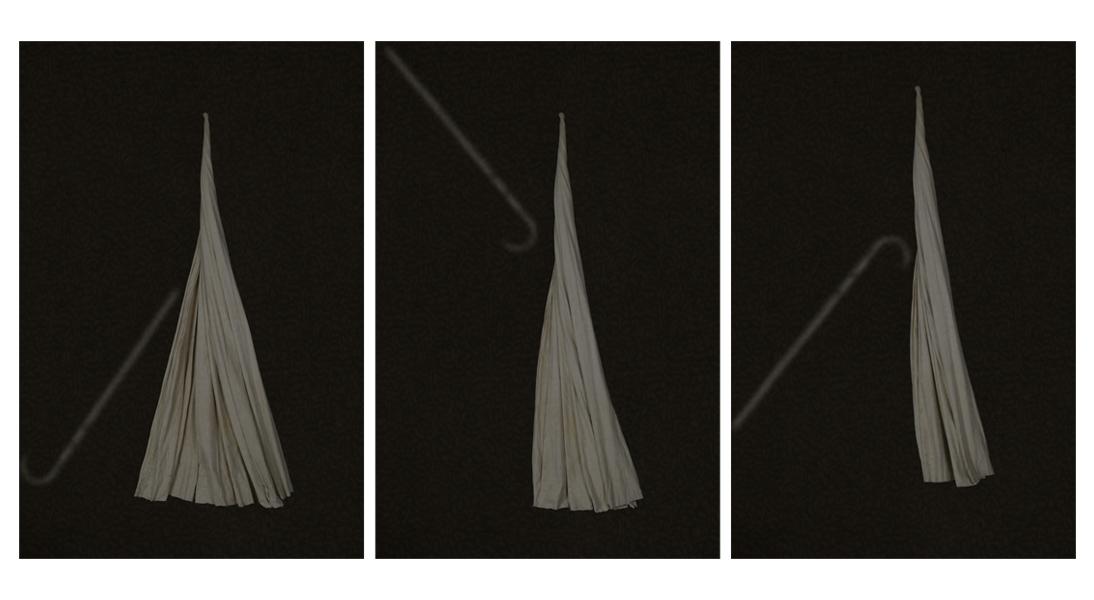

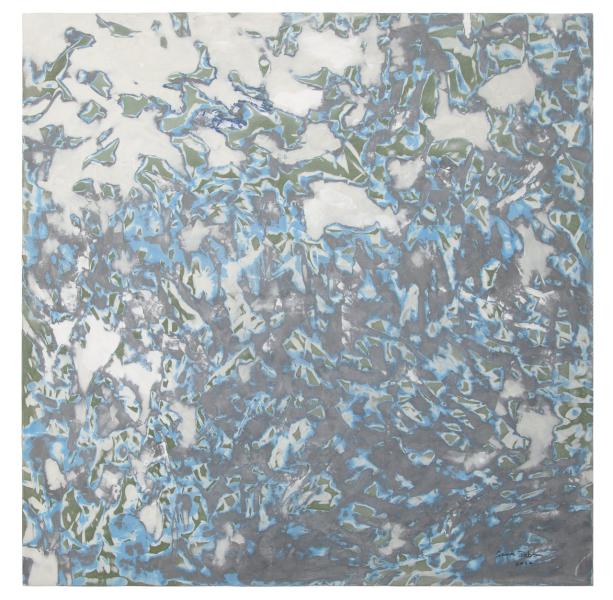

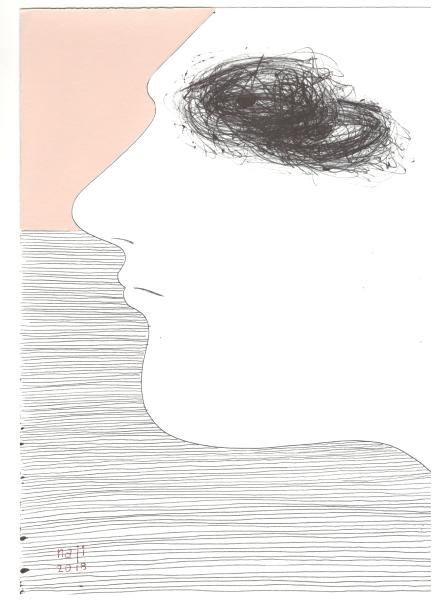

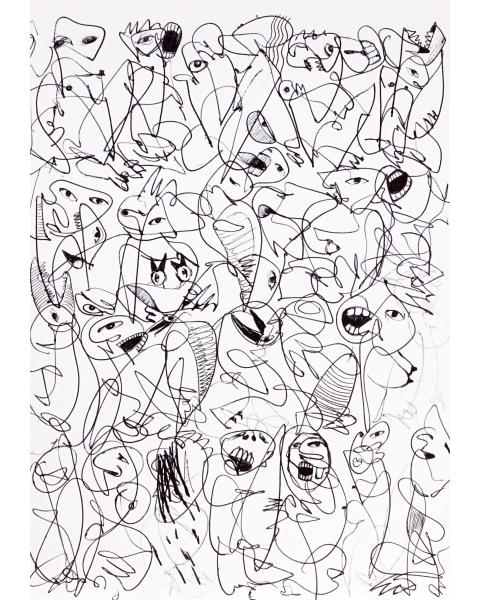

Everything in this material embodies zeft. How could I forget the sea of Gaza, which practically turned black, and the skies over our cities which grew dimmer day by day. How am I supposed to get rid of the zeft in which I have lived, if I have not tried to delve into it?

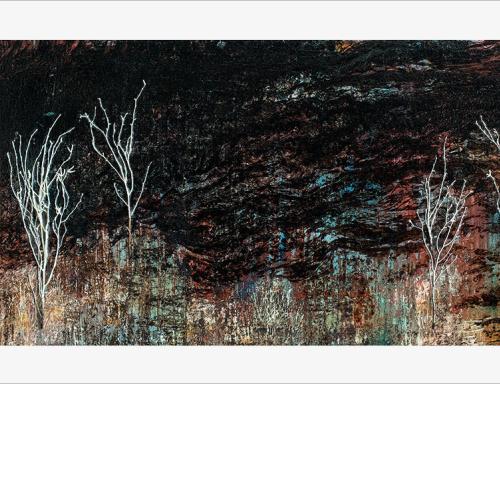

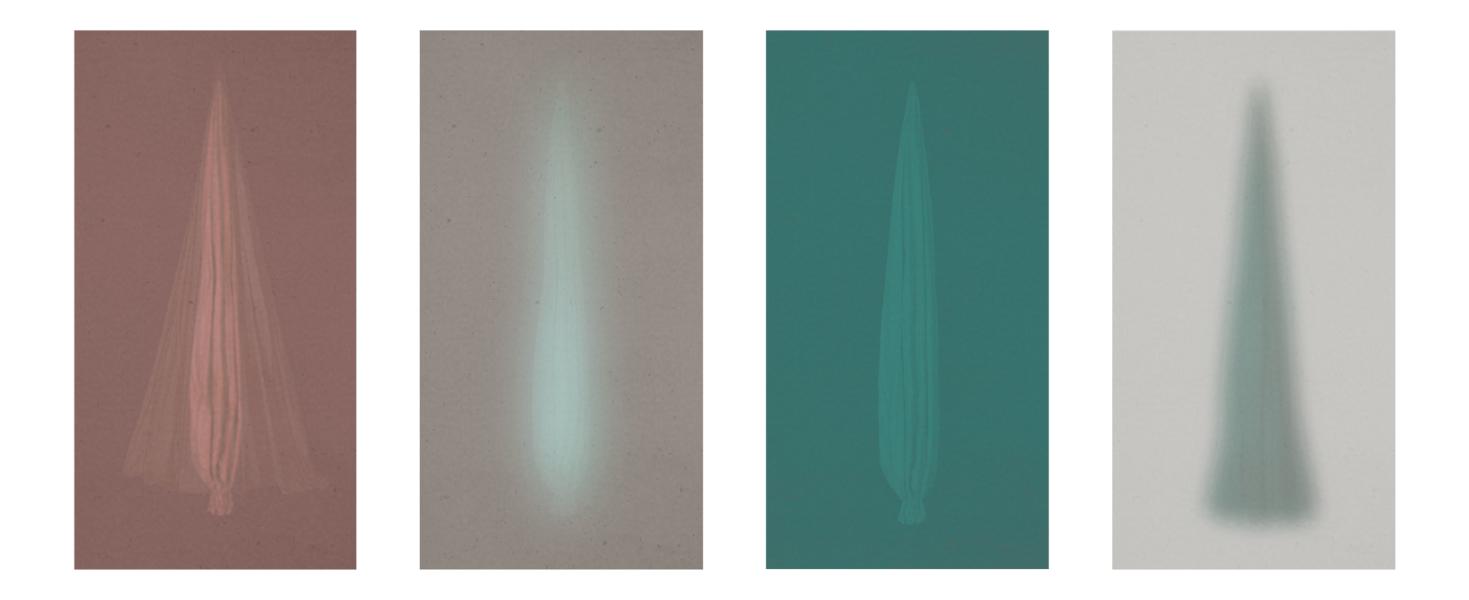

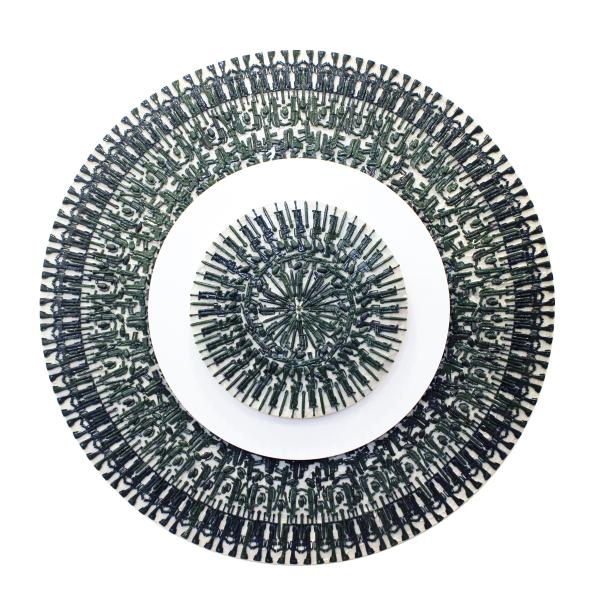

I was obsessed with the material while also feeling discontented with it, like someone who has fallen into a tar pit, without escape. This led to further research into its visual aesthetics. Now able to control it, I could express myself in a way I was unable to in the past. I was compelled towards abstraction again—the material was powerful enough. The Sea of Memories (2017) was the true beginning of ZeftLand when I shifted from the human to the earth, from the face to the landscape.

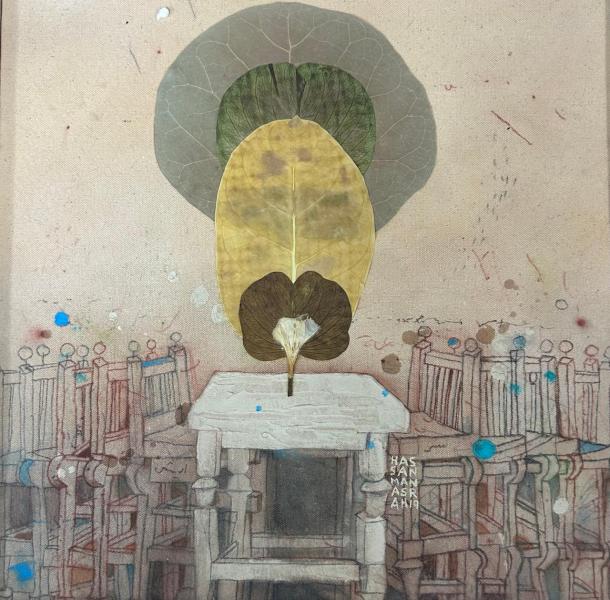

In ZeftLand I wanted to discover how to transform the character of the sacred space to that of zeft. I minimized the distance between the subject and the concept to focus on the continuous destruction of this land. And it was the land that pointed me towards using a living material, like tree branches, twigs, and dry flower petals.

These works are thus conceptual approaches to the scale of destruction, fire, and pain. I have been confronted by the sacred and the cursed, both on earth and in the work of art. I have found myself asking—is there any difference?

Hani Zurob

Feb, 2019 Paris